Fundamental questions of the human condition are worth exploring, especially at MIT, an exemplar for scientific inquiry and philosophical investigation. No endeavor is more consequential to our species' persistence than having kids, and as with many properties of humans, the answer to how many children to have, if any at all, admits different answers from different people. As fertility rates decline throughout the world, and interest in studying this issue1 rises across societal groups at large, such as the general public and various institutions, the need for data on our desire for progeny has exploded. To address this question I created a survey on number of children desired, and sent it to MIT students of all kinds2.

This is my third big investigation into the beliefs and qualities of MIT students. Previously, in spring 2023 I surveyed MIT undergraduates' 16 Personalities (MBTI); the results show clear introverted, intuitive dominance. Then, in summer 2023, after taking Prof. Dorian Abbot's Science and Christianity seminar for the UATX Forbidden Courses, I surveyed MIT-affiliated students/researchers/faculty on the strength of their belief in God and extraterrestrials, looking for any correlation between them. That analysis was written on Heterodox STEM.

Now, the truth about desired number of children (DNoC) can be revealed. What are MITers' DNOC, and what conclusions can we draw? Here's what I found.

Methodological Note

As respondents were allowed to select multiple DNoCs (e.g. "1 or 2 kids" is checking both 1 and 2), there are two ways to interpret the statistics. The first is "one person, one voice" (OPOV): if Gareth ticks 2 and 3, then both numbers count as half weight so that his total effective voice is one3. The other method is "one check, one voice" (OCOV): Gareth's 2 and 3 both count as normal weight so his total effective voice is two. I prefer OPOV, and I'd bet most of you do too. Thus, I will only use OPOV, except for the overall analysis (Figures 1 and 2).

Results: Overall Analysis

There were 510 responses. The average was 2.24 (OCOV 2.45). "Unsure" was discarded from mean calculation4, while ">= 10" was recorded as 105. The median and mode are both 2 by a robust margin. The standard deviation was 1.94 (OCOV 2.03). One sees a clear right skew in Figure 1.

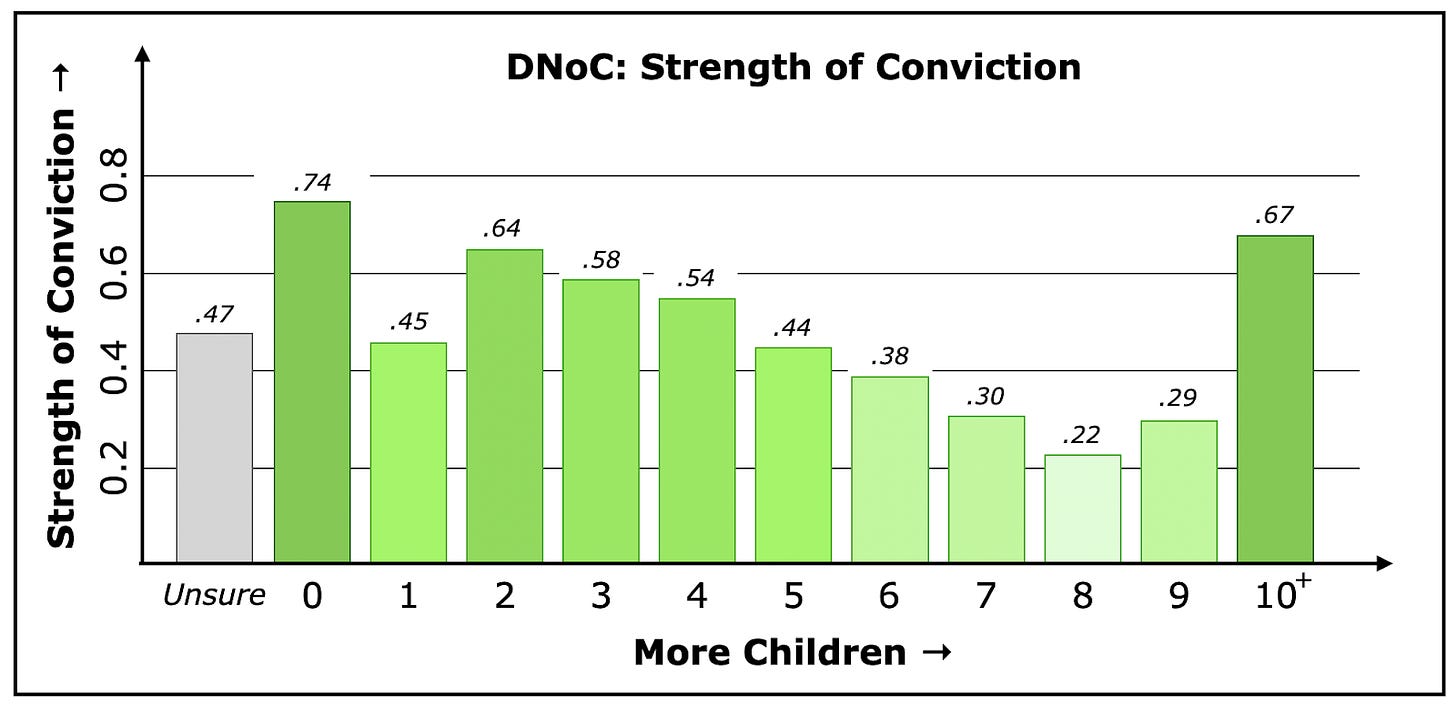

One can gauge "strength of conviction" (SoC) of having a certain number of children by dividing the OPOV value by the OCOV value: those who select a larger range are less focused on a particular number, and bring down the OPOV relative to the OCOV. The higher the SoC for a DNoC, the more convinced people who choose that DNoC are that that single number is correct. That plot looks like Figure 2.

Those who want either {zero} or {ten or more} children are most convinced in their answer, as they were least likely to also select other options6. Ironically, those undecided about DNoC were themselves undecided in this option; out of 66 people who indicated unsureness, 54 of them also selected at least one other DNoC, with 35 choosing zero; 23, one; 35, two; 15, three; and fewer than 5 each, the higher numbers7.

Gender's Impact

Women respond in much larger numbers to my personality/preference-based surveys than men; 281 females (55%) responded as opposed to 191 males (♀-♂ ratio 1.47), 26 other, and 12 gender not indicated8. Figure 3 is how the genders responded. It is worthwhile to note that if women and men responded evenly, Figure 1's bar for DNoC 0 would be significantly lower, with not much adjustment to all other values.

The magic number for women is 2: it's the mean, median, and mode (31% of responses). However, a substantial (23%) fraction of women do not want children at all, marking 0 the second-highest number, then followed by 3 children. Desiring exactly one child was not common (8%), nor was desiring four (9%); a sharp drop-off was observed between 4 and 5, with 10 of 281 (4%) women desiring at least five children. The barrier to a giant family appears to be "health constraints", as indicated by a woman who "would say >=10…as many kids as possible" but indicated 5, 6, and 7 as DNoCs. Many zero-responders were anti-natal, with comments like "Plummet the birthrate to hell" and "feels irresponsible for everyone and anyone involved." Several women indicated the difficulty of "balance with academic career" and the desire to have adopted, but not biological, children.

Men desire more children, at an average of 2.61. Two children was the clear mode, with 72 (38%) responses9, but the other peak of three (24%) also had high numbers at 46. All other responses had far lower numbers, as can be seen in the middle graph of the Figure 3 trio. High numbers—5 or more children—made up 16% of men, compared to 4% of women. High-enders had justifications of a competitive nature, like "I want to beat my parents" and "I want to have 10 kids so that there is no intergenerational decline in family size from my parents to me." Men had the least uncertainty over number of children, and by far the smallest proportion of zero-answerers (11% men, 23% women, 47% other/none).

Other gender (26) and no gender indicated (12) formed the final group. Half the respondents wanted no children; many described biological kids as a "giant question mark", with some "open to adoption."

Relationship Status's Impact

We next measure the impact of being single, dating, or engaged on DNoC. We analyze this in conjunction with gender to avoid Simpson's Paradox, and also because men and women are biologically and mentally different10. The majority of survey respondents in each gender category were single; a full breakdown is given in Figure 4. Almost everyone answered this question.

Men and women followed different DNoC averages with relationship status. Whereas men followed a V-shape, with the single at 2.64, dating at 2.51, and engaged/married at 2.85, women wanted more children as their relationships grew: single 1.76; dating 2.20; engaged/married 2.29. But for both genders, the proportion of people wanting zero children decreased with stronger relationships. For men, it plunged from 13% to 10% to 0%. For women, it was more gradual: 26%; 20%; 18%.

Age's Impact

Among all the demographic correlations with DNoC in this survey, age might be the least-researched one in general. It is difficult to decide how to bucket the ages; I wish to avoid Simpson's paradox. My approach was to equalize age buckets as best as possible, so I chose: 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24-25, 26-28, and 29. This is one of many possibilities, and our sample size is borderline sufficient but a larger corpus of responses—perhaps 4000 people instead of 510—would be ideal, as each individual has a large sway on the results. Figure 5 gives the age DNoC graph.

In the overall and male samples, there is a steady increase in DNoC from ages 18 through 28, punctuated by a sudden plunge at 21. No additional comments from the survey were written addressing age. I do not have any informal explanations as to why this happens. Perhaps it's because 21 is the legal drinking age? American culture places big emphasis on turning 21? As for women, DNoC is always stable around 2, with the dip at 21 sustained through 25 and a bump at 26-28.

It should be noted that the female-male ratio is quite high from ages 18-21, as undergraduates who took the survey were far more likely to be women: the female-male count was 166-69 (♀-♂ 2.41 ratio). But for post-undergraduates, this imbalance flips, with more men taking the survey than women, outnumbering them 108 to 90 (♀-♂ 0.83 ratio) at ages 22 and above. (14 men and 25 women did not disclose their age.) However, from Figure 5, it is not hard to see that if we equalized the two genders, the overall patterns I noted above still hold.

As age and program (SB, PhD, etc.) have a very strong correlation, if not a causal relationship, we do not perform a separate analysis for program of study. Other than undergrad SB, the other departments had too few people to draw statistically confident conclusions.

Religion's Impact

Out of 510 respondents, 358 indicated some form of religion or lack thereof. The biggest categories are: Christianity (102) and its subset Catholicism (40); None (84); Atheism (66); Agnosticism (57); Hinduism (22); and Islam (12). Among the 358, 147 identified a definite religion, while 211 indicated none, atheist, agnostic, or otherwise (including spiritual). For the few people who indicated two religions, I took the more religious between them (e.g. "Hindu/None" counted as Hindu). Figure 6 depicts the averages for various religions.

In general, the religious prefer more children than the non-religious, as is clear from Figure 6. Notably, the three major Abrahamic religions posted DNoCs of 3 or higher. With higher Muslim and Jewish (9 respondents; average 3.85) survey turnout, a more confident assessment of DNoCs for them can be drawn. Hindus at 1.89 fell well below the religious average and that of those who didn't answer the religion question. I would've loved to see where Buddhism falls on the chart, but only one respondent was Buddhist.

Among the non-religious, it is important to separate atheist, none, and agnostic, because they are not the same. An agnostic is unsure whether God (or gods) exist; a "none"-answerer does not partake in organized religion; and an atheist does not believe in God. In this way agnostics and nones are less 'harsh' than atheists. There is a common tendency in surveys to bunch "none" and "atheist" together, but as seen in Figure 6, this would be a mistake: Atheists have markedly lower DNoCs than agnostics and nones.

Religion somewhat lowers the large DNoC gender divide. The overall male-female gap is 0.63. On the non-religious side of gap 0.72 (2.19-1.47), the gap is 0.56 (1.90-1.34) for atheists, but 0.82 (2.39-1.57) for agnostics and 0.72 (2.21-1.49) for nones. Among the religious, the overall gap is smaller at 0.60 (3.22-2.62), with Christians having a 0.45 (3.35-2.90) gap, and Catholics a mere 0.05 (3.00-2.95) gap. Finally, those who did not answer the question had a 0.31 (2.37-2.06) gap.

Race/Ethnicity's Impact

Out of 510 respondents, 369 indicated race/ethnicity. The categories big enough to draw conclusions from are: White (160); Asian (131) with its subsets East Asian (29) with subset Chinese (15) and South Asian (30) with subset Indian (23); Hispanic (48); Black (27); and Middle Eastern (10). People of multiple races/ethnicities—of which there are two dozen—will count fully in multiple categories11. Figure 7 displays the results.

Whites had a relatively high DNoC at 2.47, with Blacks lower at 2.26. Middle Easterners had the highest average DNoC at 2.70, though with a sample size of 10, more responses are needed for a conclusion. Asians were lowest with 1.79. Hispanics hit the 2 threshold with 2.01, which is lower than the overall average.

If we subdivide Asians further, the East Asian average was 2.03; South Asian 1.94; Chinese 2.38; Indian 2.03. These numbers should be taken with a grain of salt, because it is very likely that large portions of those responding as "Asian" only (50 people) were Chinese or Indian. I should've been more specific in the survey. I do not know if there is systematic bias in DNoC among people who were more specific in their race/ethnicity.

The 141 respondents who did not provide a race or ethnicity averaged 2.36.

It is inconclusive whether race ameliorates the male-female gender divide. For Whites, a gap of 1.07 (3.10-2.03) is observed, the widest in this whole article. But the Asian gap is 0.33 (2.01-1.68), and the Hispanic gap 0.18 (2.19-2.01).

Conclusion and Further Research

To my knowledge, this is the first study of DNoC at MIT. With my generation entering peak fertility, the question of having children becomes increasingly important to consider. My survey was able to draw key conclusions, validating many informally-expected hypotheses (e.g. "Asians want less kids than Whites" or "The religious want more kids than the atheists"), though I would've wished for a larger sample size to perform more granular analysis.

A few people found the survey uncomfortable, and one had the impudence to tell me to shut it down. Let me reiterate that asking fundamental questions to advance our understanding of humanity, especially at one of the premier research institutes of the world, is natural and sensible; moreover, this survey was both anonymous and optional. There is nothing wrong with this survey; one who doesn't like it is free not to answer it. The research into fertility and children will not be stopped.

Footnotes

Daniel Hess of More Births at MoreBirths.com is one such site that offers research on this issue. Note: Hess is highly pro-natal.

MIT has email lists for various groups. For undergraduates, a "dormspam" system enables students to advertise events, surveys, and other fun activities. Sometimes, the same exists for graduate dorms and academic departments; there is no unified directory or guide for these. We also use Slack. I cannot guarantee that I have reached every single student, but I have received responses from a wide audience.

If Gareth chose 2 and "undecided", then both answers are of half weight.

Thus, in the case described in footnote 3, Gareth would've only contributed half weight to the average.

Given how few people selected 10+, and the biological limits of reproduction, this represents only a very slight underestimate for the true mean.

Technically there is a difference between likelihood to select more than one answer and SoC, because SoC depends on how many answers were chosen, not just whether or not two or more answers were chosen. However, the two are highly correlated, and regardless, the statement is true. I just wanted to indicate to the astute math reader that I am aware of this distinction.

5 chose four, 3 chose five, 1 chose each of six through nine, and 2 chose ten-plus.

This is closer to evenness than the ratio in my 16 Personalities survey, which had 267 (66%) female, 103 male (2.59 ♀-♂ ratio), and 35 other/none responses. The reason is easy to identify. Whereas I sent the 16 Personalities survey to just undergraduates, a substantial number of post-undergrads answered this survey. See the Age section for more details on male-female ratio with respect to age.

Technically, the count of people who indicated two kids as one of possibly many choices is higher than 72; however, we use OPOV, so all numbers in this article will be OPOV numbers.

Other/no gender was not included in this analysis due to insufficient sample size (3 dating, 3 engaged/married).

I tend to imagine mixed people as having the 'full essence' of their constituent ethnicities. Alternatively, we could have split multi-ethnic/racial people fractionally along races/ethnicities.

Since the desire to have children is largely biological and hard-wired, especially for women, it is very surprising that so many female students don't want kids. And that the difference between being religious or not makes such a substantial difference. Social factors seem to be overcoming the most innate natural inclinations.

"Among the non-religious, it is important to separate atheist, none, and agnostic, ... and an atheist does not believe in God."

Lumping agnostics into the non-religious camp alone is biased. They are also in the non-atheist camp.

It is incorrect to say just that an atheist does not believe in God. Neither do agnostics. An atheist asserts that there is no God.