The bloody turmoil of World War II took millions of lives. Victims included erudite scholars, doctors, and innovators. It fills me with profound sorrow to think about how so many brilliant minds were extinguished, knowledge and ideas lost forever. The exact extent of the setback for science and technology will never be known—it can only be guessed from the stories of prominent Jewish scholars—Albert Einstein, Max Born, Rudolf Peierls, Robert Oppenheimer, Lise Meitner, and others—who escaped the holocaust and made ground-breaking contributions to science in their new home countries. Following cases from the archives of the British organizations dedicated to helping imperiled scholars—the Academic Assistance Council (AAC) and its successor, the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning (SPSL)—Sir David Clary recounts the stories of 30 scholars from the World War II era [2]. They come from various domains: mathematics, natural sciences, medicine, and social sciences. While most stories ended in tragedy, some show examples of miraculous survival.

The stories are organized in the following categories:

Physics and Chemistry Non-Survivors

Physics and Chemistry Survivors

Top Secret Refugees

Refugees in Mathematics

Refugees in Medicine

Refugees in Biology

Refugees in Engineering

Refugees in Social Sciences

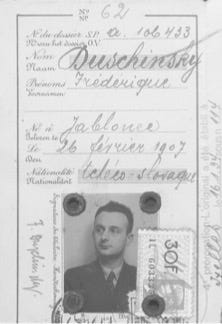

A distinguished scientist himself, Clary complements the narratives with detailed descriptions of the scientific work and important contributions of his subjects. The story of physicist Fritz Duschinsky, a Jew from Czechoslovakia murdered in Auschwitz at the age of 35, resonated with me strongly. His technique for computing molecular spectra, called Duschinsky rotation, is widely used in computational chemistry today; I myself have written a code implementing his equations. Along with many other Jewish academics, Duschinsky was dismissed from his position in Berlin in 1933 under the new laws forbidding the employment of Jews in the civil service. Despite his young age, he was already was well known professionally, but the attempts by the AAC to find a position for him in the UK were unsuccessful. In 1936, he accepted a position at an Institute in Leningrad in the USSR. It is there that he published his seminal paper “The Interpretation of the Electronic Spectrum of Polyatomic Molecules. I. On The Franck-Condon Principle.” [2] However, Duschinsky soon came to the realization that the USSR was in the grip of an ideology as deadly as Nazism. Unlike other émigrés who perished [3] in the Red Terror—such as Hans Hellmann [4], whose story is mentioned briefly—Duschinsky managed to escape and return to Europe in 1937. His brother arranged for him to come to the UK, but he was denied entry at the Croydon airport, possibly because of his connection to the USSR. Duschinsky was arrested by the Gestapo in 1942 and transported to Auschwitz. I always thought it odd that Duschinsky never followed up on his seminal paper. Now I know why...

The story of physicist and mathematician Alfred Lustig is one of a miraculous escape. Lustig was on one of the first transports from Vienna to the newly established extermination camp in Nisko, Poland in 1939. He managed to escape and found his way to the USSR, where he fought in the war, was recognized as a war hero, was untouched by the repressions, and enjoyed a long career as an educator in Yelabuga, Tatarstan.

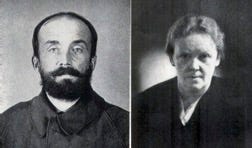

Most of the stories feature Jewish scholars, but there are exceptions. A truly unique story is that of ichthyologist Vladimir Tchernavin. He was arrested by the OGPU (a deadly organization, the precursor to the NKVD and then the KGB) in 1930 and sentenced without a trial to imprisonment in a Gulag. He served his time in Solovki, a prison camp located on a remote island in Karelia, close to the Arctic circle.

The history the Solovetsky camp was described by Solzhenitzyn in The Gulag Archipelago [5]. It is where the Gulag system was born, developed, and perfected, later to be implemented throughout the USSR [6,7]. Successful escapes from Gulags were exceedingly rare. But with the help of his wife Tatiana, Tchernavin planned and executed an escape from the camp. Along with Tatiana and their teenage son, they traveled by rowboat across the Onega Bay to the mainland and then trekked for 22 days through forests and swamps, finding their way to Finland. With the help of the AAC/SPSL, Vladimir and Tatiana eventually made it to the UK, where they found means to support themselves, albeit with difficulty. While in the UK, Vladimir and Tatiana published two books documenting their escape from Solovki and the atrocities of the Soviet regime they had witnessed: Tatiana published Escape from the Soviets in 1934, and Vladimir published I Speak for the Silent in 1935, in which he described the Soviet regime’s campaign against scientists. Unfortunately, these were not stories that the liberal-leaning intellectuals of the West wanted to hear; some examples of this self-deception can be found in Clary's book. Although Vladimir and Tatiana survived the war, Vladimir died by suicide in 1949. Tatiana died in 1971 at the age of 83.

In conclusion, Clary praises the efforts of AAC/SPSL, points out some common motifs among the stories of these lost scientists, emphasizing the inherent difficulties in providing help to scholars at risk in times of global crises, the role of chance, and the fragility of individual fates. This brought to my mind the words of Salman Rushdie, who said:

Literature is powerful, writers are fragile. Of course, we need to defend literature itself. But we actually need to defend the writers because they are more vulnerable. [8]

Indeed, the truth is indestructible, the science ultimately prevails, but the lives of scientists are fragile.

Sadly, the plight of scientists fleeing war zones and political persecution is not just a thing of the past. Consider Ukraine, where the ongoing war has destroyed infrastructure and effectively shut down scientific work. Many Ukrainian scientists have lost their homes and joined thousands of displaced citizens. At the same time, Russian scientists who have spoken against the war face persecution by the Putin government. Many Russian men, students and scientists included, have fled abroad to avoid conscription.

Organizing help for scientists at risk is crucially important—and many academic and professional organizations have come up with various initiatives. For example, RASA [9] has established a mentorship program [10] to help displaced scientists find research groups that match their expertise and to provide practical advice on networking and navigating the professional landscape in the US.

Clary’s stories of science interrupted are deeply moving, intellectually enriching, and—given the current rise of illiberal ideology worldwide [11,12]—highly relevant. The Lost Scientists of World War II will be appreciated by students, scientists, and history aficionados worldwide.

References:

[1] D. C. Clary, The Lost Scientists of World War II, World Scientific (2024).

[2] F. Duschinsky, The Interpretation of the Electronic Spectrum of Polyatomic Molecules. I. On the Franck-Condon Principle, Acta Physicochim. URSS 7 551 (1937).

[3] M. Shifman, Between Two Evils, Inference 5 (2020).

[4] W.H.E. Schwarz, D. Andrae, S.R. Arnold, J. Heidberg, H. Hellmann, J. Hinze, A. Karachalios, M.A. Kovner, P.C. Schmidt, L. Zülicke, Hans G.A. Hellmann (1903-1938); University of Siegen. Translated from Bunsen-Magazin (1999).

[5] A. Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, YMCA Press, Paris (1973). See also: The Gulag Archipelago - Wikipedia article.

[6] J. Dvořák, Solovetsky Island, Gulag online. Accessed January 7, 2024.

[7] I. Flige, Prisoners of the Solovetsky Islands. Part I: Forced Labour, Theatre and Self-Sufficiency in the Soviet Model Camp, Communist Crimes, 2021.

[8] E. Camp, Salman Rushdie: 'Literature Is Powerful, Writers Are Fragile', Reason (2023).

[9] RASA: Russian-American Science Association. Accessed January 13, 2024.

[10] Russian Speaking Academic Community: “Empowering the academic community from Post-Soviet states through mentorship while preserving a historic memory of the science diaspora.” Accessed January 13, 2024.

[11] A.I. Krylov, The Peril of Politicizing Science. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12 5371 (2021).

[12] A.I. Krylov and J. Tanzman, Fighting the Good Fight in an Age of Unreason—A New Dissident Guide, HxSTEM (2023).

Thanks for sharing with us the interesting stories of these less famous scientists. I'm wondering: Does the book also tell the stories of more famous scientists (Lisa Meitner, John Neumann, etc.)? Their scientific work is definitely not "lost", but they surely lived some time as refugees... It's also commonly agreed upon that the two specific scientists I mentioned deserved winning the Nobel Prize, but they never got it...

The soviets were a filthy dictatorship that oppressed and terrorized numerous nations and countless millions of people.

Looks like an interesting book - thanks.