(i) Introduction

I’ve been cancelled twice, in 2003 and 2019. For entirely different reasons, I’ve been in tenure trouble twice, at UCLA and at Indiana University, though I was smoothly promoted to full professor five years later (the committee chair said it was the most lightly documented and easiest case he’d ever seen), then given an endowed chair (endowed by Dean Dalton himself, anonymously), and later had that chair yanked out from under me (its funding vanished; I’ll write up the story some day). I’ve had lots of adventures with academic administrators doing strange things.

On the theory side, I’ve written a lot in law-and-economics and I wrote a much-translated book on game theory, so I’ve long puzzled over how organizations work. Eventually I hope to write up the full history of my battles with bureaucrats over the years. Here, I’ll share some lessons I’ve learned. This essay is a rewrite of a list of tips and tricks I put up on the web in 2019 on the occasion of my second cancelling. I’ll start with the cancellings. Skip ahead to section (iv) if you want advice, but hate history.

(ii) My 2003 cancelling

In 2003 Professor Eugene Volokh of UCLA’s law school asked in his blog why Christians objected more to Hindus than to homosexuals, when idolatry is a least as sinful as sodomy:

I responded in my blog, Professor Volokh responded politely, and that was that.1

Some weeks later, a student reported my blog to the Indiana University GLBT office, and immediately the staff rumor network on campus was buzzing. It’s a long story, but the upshot is that no official action was taken against me, though my pay raises over the next few years were tiny. There was no investigation and no published statement from the Administration, though Chancellor Sharon Brehm did criticize me at the start of a faculty senate meeting. Everybody was embarassed for her.2

Over the month or so of fuss, I received many nasty emails— and letters too in that bygone era (including some threatening ones)— and there were demonstrations for a while until Doug Bauder, the head of the GLBT center, visited me at my office and came to realize it was not in his interest to harass me. The local newspaper wrote an op-ed condemning me, but they allowed me to respond with an op-ed by a supporter-- the original student who turned me in, who had told me he felt guilty about turning me in. No faculty dared speak up in my support, but hardly any spoke out against me either. Many stopped me in the hallways to sympathize with me. A liberal law professor did write an op-ed for the local newspaper in favor of free speech, which I appreciated, and since nobody else did even that much, I understood why he didn’t actually mention my name. Everybody could read between the lines and know he was daring to publicly support Rasmusen, and nobody else dared do that much. That was 2003-- the age of political correctness, the polite parent of wokeness.3

(ii) My 2019 cancelling

The 2019 cancelling was harsher. Times had changed, and neither professors nor administrators still felt they had to give more than lip service, if that, to freedom of speech. I retweeted a sentence about the Big Five personality traits of psychology that I thought was interesting if correct (it lacked footnotes):4

The sentence was from an article titled, “Are Women Destroying Academia?Probably.” People focussed on the title, probably thinking I wrote it.5 Someone quote-tweeted my tweet to a site, SheRatesDogs, that specializes in stories about bad boyfriends and had something like 300,000 followers (my screenshot below is from 2023— they seem to have doubled in size). Their quote-tweet received over 29,000 “Likes”. A tidal wave of complaints hit Indiana University administrators asking how they dare employ somebody like Rasmusen.

Indiana University’s Provost, Lauren Robel, had been laying for me for quite some time, I discovered. She had a whole Eric Rasmusen file of tweets and such ready to spring when the moment was right. I think my being one of the few “no” votes cast at faculty senate meetings bugged her. She and Kelley School of Business Dean Idalene Kesner called me reprehensible, sexist, racist, homophobic, intolerant of women, disrespectful to women, intolerant of racial diversity, unchristian, vile, stupid, bigoted, and loathsome, among other things. Indiana University President Michael McRobbie and Business Economics and Public Policy Chair John Maxwell took the via masculina: complete silence while the ladies talked.

Since generally college provosts are bland and boring bureaucrats, even if sly and slick, this explosion caught the attention of the national media. For a month, things were busy. A guard was seated at a table in my office’s hallway. “I’m a female genius” T-shirts were sold by enterprising B-school students to mediocre B-school students. A bridge was painted with denunciations of Professor Rasmusen. I had fake blood dripped at home on my doorstep one midnight.

It died down in a month or so. Being a well-paid business-school professor in his 60’s, I retired a year later for other reasons, though I was tempted to stay on just because I knew people wanted me to leave. I didn’t make a deal with them, though, and, in particular, didn’t sign a nondisparagement agreement, so I’m free to Substack about it.

One reason I retired was to devote my energy to promoting free speech. Despite being a conservative, I’m Chair of Committee A (Academic Freedom and Tenure) of the Indiana Conference of the AAUP (American Association of University Professors), and, since my PhD is from MIT, a director of the MIT Free Speech Alliance (MFSA) One thing I don’t have in my list below is that if you’re in trouble, you should get help from your local AFSA affiliate (Alumni Free Speech Alliance) or AAUP chapter and contact national organizations such as the ADF, FIRE, and ACTA (the Alliance Defending Freedom, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, and the American Council of Trustees and Alumni). If you don’t have a local AFSA affiliate or AAUP chapter, start one immediately. Email me and I can get you started. Do this before you need it. Professor Abbot has asked me to write a Substack on how we put together MFSA, but it’s still in progress. I’ll title it, “How to Make Your Own MFSA”.

For now, though, on to the lessons.

(iv) The lessons

1. Good filing is essential. At the time it will seem like you are too busy to do filing, but you must do it anyway. Think of it as an investment that will start paying dividends in just three days, at which time you otherwise would otherwise spend half an hour looking for an email hastily saved somewhere in the bowels of your laptop, or maybe erased by accident. Somebody said, “If you want something done, ask a busy man to do it.” Similarly, “If you’re super-busy, that’s the time to pause and do some filing.”

Set up a computer folder called CANCELLING immediately, with a file called 00notes.doc for general stuff and one called contacts.doc for reporters, supporters, and enemies’ contact information. Create subfolders MEDIA and DOCUMENTS and OLD.

Set up a new mailbox specially for mail connected with the kerfuffle.

Keep a file, encouragement.doc, of the texts of encouraging emails, comments, tweets, and so forth. Look at it every once in a while to keep your spirits up, and show it to the public too (without identifying information that might compromise your supporters) to show how numerous and reasonable your supporters are. You may also wish to make a public list of critical emails, to show how numerous, dull-witted, and obscene your adversaries are. For me, the contrast in quality was incredible.

Keep a file, threats.doc, of the texts and contact info of threatening or psychotic emails, in case the police need it later.

Create a file like this one, lessons.doc, for lessons you’ve learned or advice you might give, including mistakes you’ve made. It’s important to learn from experience and you will forget useful little things later.

2. Tell reporters you will answer their questions on email and talk to them on the phone but make sure that if you speak on the phone or live it will be for background only, no quotes. Journalism has customs you need to know about. If you don’t say it’s off the record, it’s on the record, and it’s fair for them to print anything you say. If you say it’s off the record, it’s off the record, and I have found them to indeed keep it off the record. There are other fine points of phrasing, e.g., “for background only” or “not for attribution”. It’s up to you to make it clear— AT THE START OF EVERY CONVERSATION— what the rules are. It’s fair game, I think, for them to call you back to restart the conversation under zero restrictions.

Remember, they are playing a game with you, and you have different objectives. It isn’t a zero-sum game, because it can end up win-win or lose-lose, but your job is to make sure it’s win-win, unless you’re trying to get revenge on the reporter for previous offenses, in which case you aim for win-lose.

If you are a conservative, it is best to assume that the reporter is out to get you, to make you look bad and humiliate you. The regime media is like that. With any reporter, you should assume they are looking for the most interesting thing you say. If you make a blunder, that is usually interesting. If you say something and immediately wish you hadn’t said it, that is extremely likely to be the most interesting thing you’ve said, and it’s what they’ll use. One way to think about it is that if they favor your side, they will use the 10% of the interview you most want them to use; if they favor the other side, they will use the 10% you least want them to use. Even if you are conservative, there are actually outlets that will favor you; it’s just that they will be outlets you’ve never heard of, like The College Fix, rather than CNN or The Los Angeles Times.

Think about using Zoom in preference to the telephone. Recording becomes easy, and you want to see the reporter’s face, and for them to see yours, so they think of you as a human being with feelings and family.

Have a prepared statement for reporters. Often this is enough. A FAQs webpage might be a good idea too.

Reporters do like each having their own, unique, statement from you. So offer to rewrite it especially for them.

Always return inquiries from reporters within an hour, and ask them what their deadline is. You don’t have to answer their questions quickly; you just need to be considerate to them and pick a mutually suitable time to reply.

Ask reporters to send you a copy of anything they publish on you. Some will do the polite thing and send it to you, most will not. Don’t ask to see their story before they publish it so you can check for errors. Even if they would like this, which usually they would (few intend to make errors of fact), journalism moves too quickly for that be practical. They will finish writing at the last minute, then their editor will change it, then someone will change it to fit the available space or make room for a new ad.

Keep a list of reporters who have contacted you, with their contact info. If you have time, google them and find out whether they are honest or slimy, friendly or hostile.

Media outlet such as the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, and Washington Post contract with local photographers to take pictures. If a photographer comes to take pictures of you, beware of shots from low upwards. Those are less flattering, and are sometimes used to make the subject look threatening. Take all keys, change, and phones out of your pocket. Make sure the back part of your necktie is behind the front. Wear nonreflective glasses that do not turn dark in the sun. Don't let your hands hang-- put them in your pockets or on your hips or something. Ask if you can have copies of the shots; you may be given them for free. A Washington Post photographer did that for me recently, and she told me to do many of these things, a reliable sign that the Post had not told her to make me look bad.

Be prepared to make your own videos, professional TV quality, with questions the stations would like to hear about. I did that in 2019, having my 16-year-old daughter ask the questions. The station could edit her out and substitute their own reporter as the questioner. You can even ask them what questions they want asked, but remember that you don’t have to do what they want; it’s a matter of bargaining with you making the last offer.6

Do what I've done for teaching: have an 8x11 page with what you need to always remember to do in advance of speaking to an audience:

A. Speak slowly.

B. Pray.

Another of my daughters suggested a third instruction:

C. Smile

She says my smile is good. If your smile is bad, don't smile. Lots of these lessons have to be adapted to your own personality.

One example of a mistake I made was not to put top priority on replying on the web to the Provost’s false attribution to me of three political opinions in her memo. I let the evening go by and only started addressing that the next morning. Things move much faster even than in litigation. You don't measure deadlines in days, but in hours.

3. Set up a webpage. This should have your statement at the top, a brief explanation of the kerfuffle, contact info for reporters, links to documents, and links to media. See http://www.rasmusen.org/special/2019kerfuffle/ and http://www.rasmusen.org/citigroup/. The second is for a lawsuit, but any kind of public controversy contains the same elements. Put your encouraging emails here, anonymized and redacted for anonymity. Include a good photo of yourself and say there it is in the public domain so anybody can use it without fear of copyright infringement. Post a short video of yourself so the media can see if you’re ugly and incoherent or not. Include a one-paragraph bio and a one-sentence quote that would be useful in an article somebody writes. Think about including a list of experts, friends, or honest enemies who could be phoned for comment. Honest enemies are to be included because thorough reporters do want to hear both sides of the story, and if you don’t give them an honest name, they’ll phone up somebody dishonest.

Always keep in mind that your reputation starts in a heavy deficit, a negative position. The general public reads The New York Times and thinks you are a crypto-Nazi who likes to torture small animals and listen to country music. Wokedom is against you, and the media in particular. This should make you feel free. Anything you do is likely to improve your initial position at the bottom of the basement. If you start off with a reputation of -100 and you give a -10 performance, you’ll end up improving your rating to -55.

You should not utterly refuse to help hostile media write their articles or do their videos. Video of you helps, other things equal, because it shows you as a human being rather than an inhuman monster, eight feet tall with green scales and fangs. They will try to make you look bad, but just by giving you exposure, they will help. You must, however, be very careful of what you say and assume they will only use the worst five seconds or two sentences unless it is a media outlet you know to be friendly to you. Those do exist, and the strategy with them is utterly different, because they’ll only use the best five seconds and two sentences.

Think of the reporters as human beings, not as a mechanical tools of an organization. Their interest is different from their employer’s. The New York Times wants to destroy you. The New York Times reporter might have this on his list of objectives, and he wants to please his boss, but he wants to get his story done as quickly and easily as he can, he doesn’t want to look stupid to readers, he wants to put interesting things in his story, he wants to impress other reporters, and he wants to impress potential future employers at other media outlets. In particular, he wants to be nice to people he meets, such as you unless you anger him with insults, even though he will often sacrifice niceness for his other objectives. You must take advantage of what economists call “the principal-agent problem” or “moral hazard”.

Realize that it is okay if you look foolish. Don't be proud. Your job is not to look good in the usual, worldly, way. You don't have to look like a movie star or talk with the glibness of a news reporter. Your objective is to tell people what the truth is, with a personal appearance that will make them believe you. What you want to look like will vary depending on your circumstances. I, for example, almost never would benefit from looking like a movie star. Instead, I might benefit from looking like an idiot savant or an absent-minded professor or a high-functioning autistic or a Midwestern hick with a veneer of education or a polymath Yale-MIT grad. Maybe I *am* one or all of those things. They are all okay for hindering people from demonizing me and for making people believe I am sincere and good-hearted.

4. Have telephone voice recording software installed if you are in a state where recording without notice is legal. In any state, tell reporters you are recording. Do that even if it is off the record, so you can prove they knew it was off the record, and in case they claim you said something you didn't. This is more of a danger with low-level reporters (e.g., college student newspaper reporters) probably, but I don't know. Reporter quality varies tremendously.

Also, record any conversations with university administrators. They lie without compunction, and you need to be able to prove it. (“How do you know whether a dean is lying?” His lips are moving.”)7

5. Some of your friends and colleagues will wonder if you're crazy and will think you very foolish to poke your head up and expose yourself as a target. This is especially true of non-Americans. People from France, or China, or pretty much anywhere except anglophone countries, have grown up with the idea that of course you are going to get in trouble if you say certain things publicly, and everyone but an idiot knows you can’t just say what you think.

Write up an explanation for them, so you will know what to say. A video or audio version should also be available, since many people are effectively illiterate-- if it's written, they'll skip it. I didn't do that, because I thought it was something that could wait, and then the public controversy subsided. But it's something that can be done in advance if you think this will happen to you someday, as I'd been thinking for a long time without doing this kind of preparation. Eventually wokies will find one thing or another that you say or write, and you can't know in advance what will trigger them. I’ve written much more inflammatory sentences myself than the sedate quote that got me into hot water in 2019.

In advance, if you know that you might be a target, prepare a short, 100-400 word statement of “What it means for me to be a Christian” (or Moslem, or Conservative, or Black Woman). Link to this prominently from your controversy webpage.

6. Let people help you. It's like when there's a death in the family. Everybody wants to help, but they don't know what to do. Don't worry about wasting their time. They will feel better if they can help out in any way whatsoever. Don't be too proud to ask for help, and don't think you are imposing on them. This is hard for me personally.

Look for people who will be built up by helping you. Pick someone you think needs building up, and ask them to do something, and keep them in the loop especially. This is not for help with the situation; this is an example of making use of the situation to do something else that's good.

Get children involved— yours, of course, but also any other children who’d like to be of use. They can be very helpful in looking for typos, checking your appearance, and fixing up webpages, and it will be educational for them.

Figure out how to get help. What can other people do for you? (e.g., let you know of articles and blogposts, draft replies to emails, write to politicians). Think, "If someone asks me how they can help, what will I tell them do, specifically?

From the start, have someone whose task it is to monitor media articles, blog posts, comment sections, and bulletin boards. This person should note errors and lies and comment on them and email authors and publications. He should also plaster the address of the controversy website everywhere, once at least in every comment section, so people know where to get reliable information. Unless this is done, errors will propagate and grow, as everybody starts quoting the bad source and then they, perhaps more reliable, get quoted, and it gets into comment sections, and so forth. Rumor has a thousand tongues, but if you throw hot pepper on the first one, he’ll be chastened.

Get political connections, especially if you are at a state university. Think of what connections your friends have. In advance, think about visiting political events of both parties and getting to know a few folk there.

7. Take lots of naps, watch lots of TV, get lots of exercise. I violated this by not jogging after the first three days, but later I went back to it.

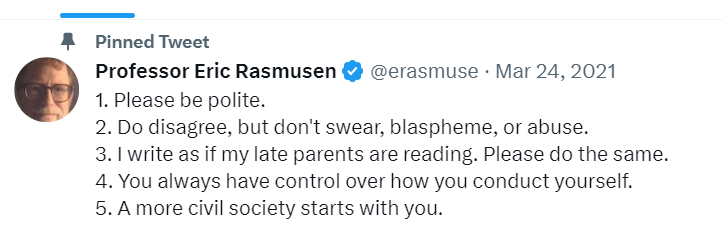

8. Think about rebuking rude comments about your adversaries. A friend told me after I published an essay in the Unz Review calling for Provost Lauren Robel to be fired that the very first reader comment was a derogatory remark about her personal appearance and I ought to reply. So I did, having my wife and daughter select comments that needed admonishment. This also teaches manners to the Internet crowd, many of whom have never heard of them so adopt a pedagogic tone rather than a combatative one.8

9. You need to have some name to call your situation. I am not satisfied with any of the terms commonly used. “The Rasmusen Situation”, “The Rasmusen Controversy”, “The Rasmusen Crisis”, and “The Rasmusen Affair” are all unsatisfactory. “The Rasmusen Kerfuffle” was created to apply precisely to this kind of situation, but kerfuffle is an ugly and awkward word. I welcome comments on this point. “Cancelling” is also a bad term, since the literal meaning is to successfully obliterate rather than merely to attempt to do so, but it seems to have become established.

10. Don’t worry too much about death threats, or threats to harm your children or to sodomize you. That kind of stuff is to be expected if you’re cancelled by the Left. Consider these three people:

Joe, who really does intend to kill you.

Mike, who not only wants to kill you but to boast about it.

Wayne, who just wants to scare you.

Joe will not email you telling you he’s going to kill you. He’ll just do it.

Mike might email you, but in addition he will post a message on Twitter or on a billboard telling the public that he’s going to kill you. This vastly increases the chances he’ll be caught, but he’s willing to risk that to get the publicity.

Wayne will just email you, because it’s easy and he wants to scare you and to feel like a dangerous man, the kind who does kill people, even though he lives in his mom’s basement and plays video games all day.

So if someone sends you a threatening email but doesn’t let the public know, it’s Wayne, not Joe or Mike. You’re safe.

Nonetheless, keep a file of all threats. It’s easy to do. And even the threat is actually a crime, so if you are good with computers, you could track down the threatener and turn him in.

You probably should get some weaponry. After a midnight blood-on-the-threshold incident at my house, I bought two guns. I also possess a variety of bladed, chemical, and “other” offensive and defensive devices. Tell people about the guns— I am being a bit meta right here and I talk about them on Twitter.9 My wife has shot the guns too, so be warned, hostile reader. She hasn’t used them much, but that just means that when she aims for your leg she’ll probably hit you in the chest. Both you and she would be sad then.10

The best weaponry, though, is pepper spray and a whistle, which you should own anyway and always carry if you are a woman (just a couple of weeks ago I was telling this to my 7th-grade math students). These will deter almost all attackers and hurt them only temporarily. That matters because (a) you probably don’t want to kill them, especially if you’re of the gentler sex, and (b) if you had a gun you might just stand there with it because you don’t want to kill anyone. Pepper spray is also small, light, and cheap; a whistle is useful on many other occasions.11 The only drawback is, neither is much use against tin cans and rabbits.

I also put up the sign in the picture below. If you do the same, be sure and put it in the back, not the front, since you don’t want deliverymen dropping their packages.

I decided *against* asking the University for protection against threats of violence. I had a couple of them, but it I didn’t feel like I needed professional protection. I did take the precautions I described.

11. If you are offered a non-disparagement agreement (an NDA), do not sign it without heavy thought. A common pattern is for a university to mistreat a professor unlawfully knowing they'd lose in court, but intending to settle for money damages. A good example is when they fire a tenured professor for political speech, but they do this in lots of non-political situations too. I think there’s standard handbook for university administrators that tells them to do this. They have to pay maybe $100,000, so it becomes a question of whether the university president wants to pay that much to satisfy his personal spite. Part of the playbook is to include an NDA in the agreement so the victim won’t report the waste of money to the press, or reveal other bad things the university has done. Anyone who’s been teaching for a while knows a lot of things university administrations don’t want the Trustees to hear about. The NDA is extremely valuable, often more valuable than the amount the university expects to lose in court, but victims and their attorneys often don’t realize that and give it away for free. They should realize that if they would win $400,000 in court with 90% probability, they shouldn't settle for less than $360,000 unless they are extremely risk averse. They should realize that even $360,000 is low, because the university probably would have to spend a lot more on legal fees than they would (another reason universities bargain better). Most important, victims should realize that the NDA is probably worth just as much as the main settlement amount. If you settle for $360,000, and the university says, as an afterthought, "Oh, and how about we both sign an NDA?" your response should not be "Sure", but "OK-- how about an extra $400,000 if I agree to sign?". Think of a car salesman who gets you to agree to pay $24,999 for a car and then casually suggests you finance it at a 20% interest rate.

In case I had been fired, I had a $500/hour, nationally-known, lawyer ready to sue Indiana University, and I was fortunate enough to have a business-school-level salary, so it would have been very expensive for them (the judge would have awarded me attorney’s fees too). But they didn’t fire me, and defamation lawsuits are unpleasant and obsessing, so I decided, reluctantly, that I should turn my energy in other directions.

12. Attend to your Wikipedia page. If you didn't have one before, you probably will now. You can comment in the Talk section, but its bad form to edit the article on you yourself. Instead, find a friend or, better, a neutral, who is willing to correct falsehoods. Also, it’s best to have it written an an Event page, not a Person page. Gordon Klein had a page that was taken down because he was not notable, some Wikipedians said, except for one event— being cancelled. That is debatable, but if the article had been titled “The Suspension of Gordon Klein”, it would have passed muster. Lefty Wikipedians will try this with anyone— see Eric Rasmusen-Talk and Dorian Abbot-Talk. See also George Floyd-Talk for the exception of “If the event is highly significant, and the individual's role within it is a large one…”— but really an Event article is the way to go, e.g., “Killing of Eric Garner”.

(v) Conclusions

Are you feeling overwhelmed? Of course. Just go step by step. I’m not sure how to prioritize all the advice I’ve been giving. Filing, taking care of your mental health, and getting help are maybe the most important three things. Good luck, and Godspeed.

I’m embarassed about it, but I can’t link to my own blog post. For technical reasons mysterious to me, that blog stopped working a few years later. I could probably dig it up, but I don’t know Php and databases and such, so it would be a major chore. I wrote my blog in raw HTML at the time rather than blogging software, making it even messier. In 2008 I did copy the post and some further ones in a long post chronicling the 2003 incident.

One of the faculty leaders came up to me after the meeting and assured me I didn’t need to make any fuss, because the Chancellor wouldn’t be lasting long anyway. She was saying other odd things and her Chancellorship did end before her term was up. By seven years later, she realized she had Alzheimer’s, which may have been part of the problem.

I’ll write the story up more fully some day. Judge Richard Posner was a co-author of mine with whom I was on the Board of Directors of the American Law and Economics Association. I remember coming into the room at the annual directors’ meeting and him saying in his high-pitched voice, “You know, Eric, you’re wrong.” But that’s just like the disagreement we had on many different things, and to be told you’re wrong by as good a scholar as Posner is actually something of an honor, especially if it’s him who’s wrong and not you.

The Big Five are Extraversion, Conscientious, Openness, Neuroticism, and Agreeableness. I, by the way, am near the population average except for being high in Openness. The Big Five is the standard, principal-components, paradigm in academic psychology, though more readers have probably heard of the Jungian Myers-Briggs Extraversion-Intuiting-Thinking-Judging paradigm. Looking at the quote about geniuses again now, I think the author was just venturing the thought as his own opinion rather than reporting a scientific result. But it sounds correct, even if was just conjecture.

Even the Washington Post ascribed authorship of the article to me and had to make an embarassing retraction. It was a natural, if sloppy, mistake. How could there be so much fuss over a professor just quoting a sentence of somebody else’s about academic psychology? It must be that he wrote the article. But no.

Rather than explaining last-offer bargaining here, I’ll refer you to Chapter 12 of my game theory book. Whoever gets to make the last offer essentially gets to make a take-it-or-leave-it offer. The media outlet takes it as you give it to them, or not at all.

I wonder if feminists think I should have phrased that as “Her lips are moving.” I am using the impersonal “his”.

Dean Kesner seemed pretty upset after I wrote in my Unz Review article,

If the Provost is saying bad things about me in meetings or phone conversations, making private claims as false as her public claims, I hope somebody records it and sends it to Mancow Muller. Indiana is a “one-party consent” state meaning only one of the parties in a meeting or phone call needs to know a recording is being made. If you’d like to help, think about that. Of course, my field is game theory, so one reason I’m saying this is that I expect the Provost to read it too, and consciousness of the danger will help her avoid temptation, an even better outcome.

She said that she was going to record our conversations after that. But of course I’d done some recording already. If I haven’t erased it by accident (I’m not as slick as I sound), I might post some audio some day, as Julie Moore of Taylor University did this spring when her provost fired her using a cowardly pretext. Remember what Machiavelli said about love and fear, and how much easier it is to move a bureaucrat’s heart to fear than to love.

There are honest deans, of course, just as there are honest used-car salesmen and personal-injury lawyers, but certain vocations present strong temptations to lie. All the more glory to those who resist. I hear that one reason Elena Kagan was appointed to the Supreme Court so smoothly was that everyone said she was an honest Dean of Harvard Law School. A woman who survives such a job with her virtue intact is a virtuous woman indeed.

(1) “@dearieme, you should not talk about a lady like that. Think about deleting.” (2) “@Biff, this is both rude and useless. Delete it and replace it with something better.” (3) “Don’t be rude, @Goetz. A gentleman does not talk about a lady’s looks.”

Cf. the 1964 movie Dr. Strangelove, beloved of game theorists:

Russian Ambassador Alexei de Sadeski: No sir. It is not a thing a sane man would do. The Doomsday Machine is designed to trigger itself automatically.

President Merkin Muffley (Peter Sellers): But surely you can disarm it somehow.

De Sadeski: No. It is designed to explode if any attempt is ever made to untrigger it….

Muffley: But, how is it possible for this thing to be triggered automatically, and at the same time impossible to untrigger?

Science Advisor Dr. Strangelove (also Peter Sellers): Mr. President, it is not only possible, it is essential. That is the whole idea of this machine, you know. Deterrence is the art of producing in the mind of the enemy... the fear to attack. And so, because of the automated and irrevocable decision making process which rules out human meddling, the Doomsday Machine is terrifying. It's simple to understand. And completely credible, and convincing.

General Buck Turgidson (George C. Scott): Gee, I wish we had one of them Doomsday Machines, Stainsy….

Strangelove: Yes, but the... whole point of the Doomsday Machine... is lost... if you keep it a secret! Why didn't you tell the world, eh?

De Sadeski: It was to be announced at the Party Congress on Monday. As you know, the Premier loves surprises.

Well, I guess you wouldn’t. You’d be dead.

E.g., at the end of the American Law and Economics Association conference’s second day one year, two hundred or so professors were talking loudly over drinks in a crowded room and Karen Crocco just couldn’t get their attention to announce that it was time to go to dinner. I pulled out my whistle and blew it loudly. Immediately— utter silence. Half a second later, universal laughter followed when they saw which well-known eccentric had blown the whistle, but Karen was able to make the announcement.

More often, a whistle is useful if you have children who wander off or need a warning when you are not close by. I don’t advocate the naval system used in The Sound of Music, however. You mustn’t treat children as if they were law-and-economics professors.

See also Lee Jussim's https://unsafescience.substack.com/p/my-vita-of-denunciation

and my later

https://ericrasmusen.substack.com/p/good-news-for-the-cancelled-club

I just came across something I'd add to the essay above:

13. Don't worry about what strangers think. They aren't thinking about you at all. Everyone is busy thinking about themselves. Except maybe your parents and grandparents. Which is why you should call them often. **Wink wink** (https://twitter.com/FoundationDads/status/1726604551342428454)