This is a portion of Garett’s address to the Intellectual Freedom of Navigation Conference held at the University of Chicago on November 8, 2025. Further elaboration here in Garett’s essay for the Routledge Handbook of the Ethics of Migration edited by Sahar Akhtar.

I’m here to talk about immigration policy.

Let me start with a policy lesson up front—before I prove these claims. I’m just going to use a short syllogism.

First, our neighbors shape us in multiple ways. One is through peer effects—where we all become a little bit like our neighbors. There’s a nice study that I mentioned in one of my books where it finds that—if your neighbor wins the lottery and buys a nice car—you’re more likely to buy a nice car yourself. Basically—random events that happen near you cause some spending—they can make you spend a little bit more. That’s just one tiny example of something that we all know—which is that our neighbors can shape who we are.

A more important way in which our neighbors shape us is that our neighbors are the people who shape our government. They may be bureaucrats in our government, and they may be people voting for our government if we live in a democracy. Either way—our neighbors are going to shape our government. Our government has an enormous effect on our productivity. I think those are both pretty uncontroversial statements.

The second statement also cannot be controversial—which is that immigration gives us new neighbors. Those neighbors might be better than us—they might be worse than us. I hope they’re better than us.

Therefore—that’s the third statement—we should choose these new neighbors wisely, because those neighbors are going to be shaping how we live. Preferably, we’ll choose those new neighbors wisely using the best modern social science.

My next claim here is going to be that immigrants can hurt government quality. I’m going to use a very important and [ironic tone] very controversial example of this—which is the Confederate diaspora. One of the co-authors of a paper with this title actually spoke at George Mason a little while ago—talked about a different paper—but this research on the Confederate diaspora—this particular paper got quite a bit of media attention at the time.

It turns out that when Southern Confederates after the war moved to the North and to the West—they carried their attitudes with them. There was attitude migration. According to the best efforts of these scholars, the places where these Confederates moved to ended up with more racist—more bigoted—policies. They were more likely to have things like sundown laws—or more likely to have race codes in housing—and a variety of other outcomes including sociological outcomes like arrest disparities, economic disparities, but also importantly, government rule disparities. If a lot of Confederates show up in your neighborhood, they’re probably going to hurt your government, at least over the long run. That’s the best evidence we have right now.

This got a lot of attention online. NBC News had a nice piece about it. Somehow it never got discussed on Econ Twitter. I think I know why—it would have been too obvious what it meant for immigration policy.

The Great Migration is another example—that’s the great migration of African Americans from the South to the North, as they flee some of the most bigoted institutions imaginable. Again—moving to the North and to the West. A nice paper—nice academic paper—shows that when African Americans move to the North and to the West—they change the views of their neighbors. When African Americans move to the North and to the West—it turns out that in those places, whites were more likely to become favorable and sympathetic to civil rights movements. It turns out that the members of Congress in districts where African Americans were likely to move to in large numbers became more likely to actually support civil rights movements.

As many of you know—it was white Republican members of Congress who were disproportionately likely to support the Civil Rights Act—the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Part of the reason for that—according to the best research we have—is that the Great Migration occurred. The effect on voting behaviors was bigger than you can predict from just the narrow effect of the increase in the Black vote in those areas. It turns out that support for civil rights is—mercifully—contagious. Mercifully contagious. You see somebody—you’re like—”Oh—I hadn’t thought about this issue for a while—but now I’ve got a neighbor down the street.” It turns out that people’s ideas are politically contagious. By getting new neighbors—you’re getting new political opinions.

Again—this is widely discussed online—never discussed on Econ Twitter.

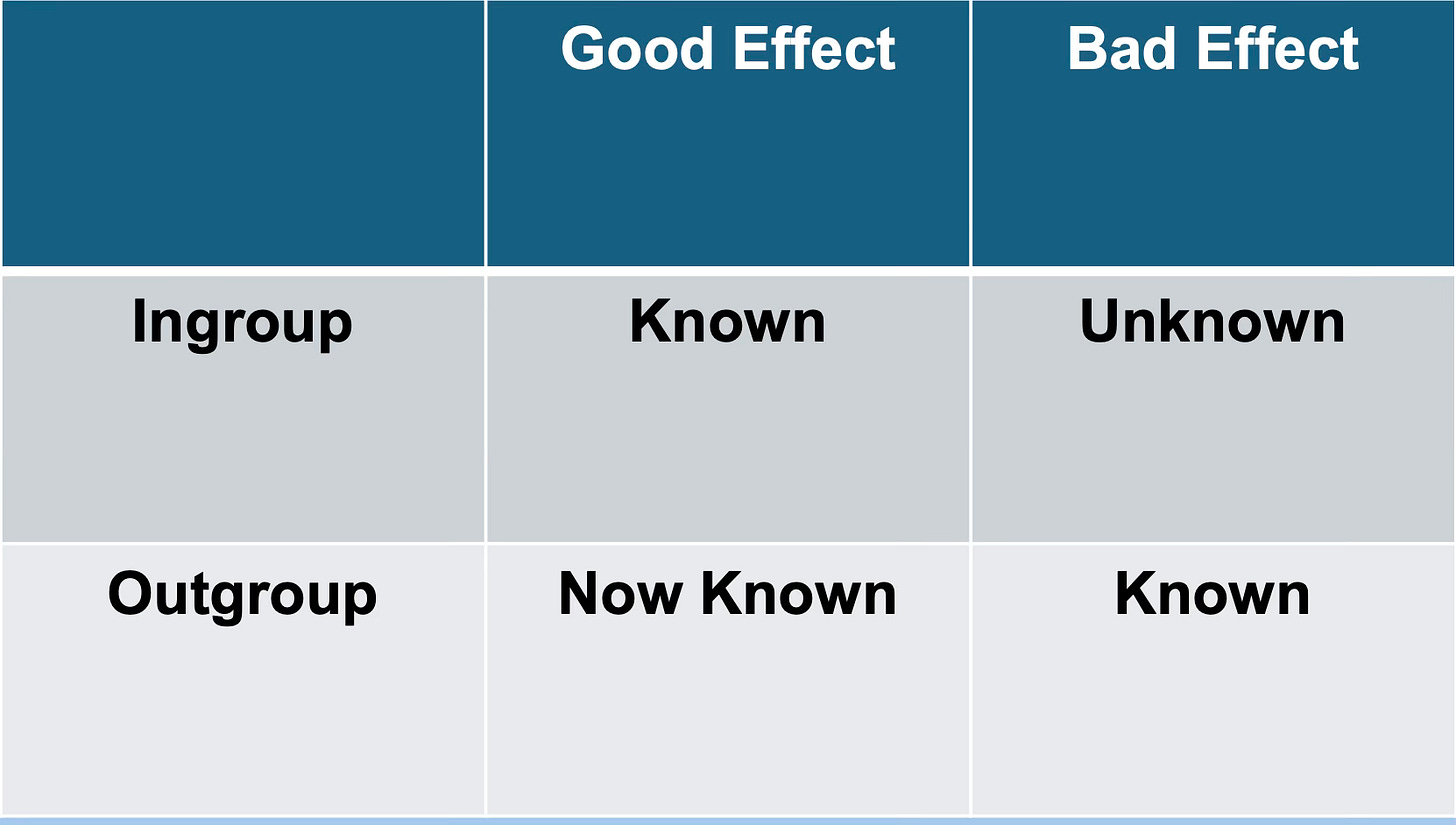

If we’re trying to study the question of how immigrants can shape government quality—according to the best published scholarly research, I’d like to do what I was taught long ago by Ted Lowi at Cornell—which is put everything in a 2-by-2 framework if you can.

The x-axis works this way: immigrants can have a good effect on the institutions—or they can have a bad effect on the institutions. The second issue—the y-axis here—is whether immigrants are members of an in-group or members of an out-group.

We know now that if immigrants are members of the in-group—they can have a good effect on institutions. That’s what the Great Migration taught us. You see the Great Migration of African Americans—that’s migration of an in-group. Of course—we’re in academia—we know that African Americans fleeing the terrible institutions of the South—those people are part of the in-group. Confederates are part of the out-group—right? They’re part of my out-group. They might be some of my ancestors—I’m not sure—23andMe hasn’t gotten quite precise enough yet, but personally, they’re part of my out-group.

Those two forms of migration have been studied. We know that in-group can have good effects. We know the out-group can have bad effects. We don’t know about the other two boxes very much—because they don’t get studied. Funny how that happens.

But in my books—Hive Mind and Culture Transplant—I like to be a person who focuses on positives when I can. I found some instances where out-group has had some good effects on institutions.

In Culture Transplant in particular I talk about how the migration of the Chinese diaspora across Southeast Asia probably made Southeast Asian institutions better, and raised the productivity of the non-Chinese people around them. Chinese immigrants who moved to Malaysia—to Singapore—to the Philippines—they and their descendants didn’t assimilate to the low-quality productivity norms of the places they moved to. It’s well known that people of Chinese descent are disproportionately likely to be billionaires across Southeast Asia. What’s a little bit less known is that there’s a very strong relationship between percent Chinese and normal libertarian measures of institutional quality and of national prosperity.

That’s just one example where it looks like out-group—people who many folks aren’t entirely sympathetic to—can have some good effects on institutions. I’m still worrying about that upper-right-hand corner though: can migration by in-group make government institutions worse? Somehow that’s not getting studied. You can imagine academia is not really chomping at the bit to study that issue. But for brave young scholars, I have some ideas for future research in one of the last slides.

History’s run a few natural experiments on immigration—and often they’re very evil natural experiments. One of the good things about being an economist is that we’re allowed to learn from evil natural experiments. We don’t say—”Oh—well—that data was generated in a really evil way—so we’re not allowed to run a regression on it.” We still run the regression anyway.

The post-Columbian movement of people around the world after 1492 created a vast natural experiment. Since I just have a couple minutes, I’m going to talk just about the Americas. Before Columbus—if we look at just the Americas here—the places that were closer to the poles were further from the world technology frontier. If you ask—”Before 1500, where in the Americas are the most technologically sophisticated places?” They’re the places closer to the equator. The Aztecs, the Incan Empire—both kind of close to the equator. The high-technology places were not close to the poles.

The things you see in great museums of the world that focus on pre-Columbian technology are going to be showing you stuff made by societies that are closer to the equator.

But then after Columbus, something changed. And now the high-productivity places tend to be closer to the poles—and that’s not just in North America. Something that doesn’t get a lot of attention is that in South America, the places that have the highest income per capita are the places closest to the South Pole. Argentina gets a lot of negative attention—it’s easy to beat up on them. People tend to beat up on the global economy’s B students—more than the economy’s D students. It feels like punching down if you beat up on the D students.

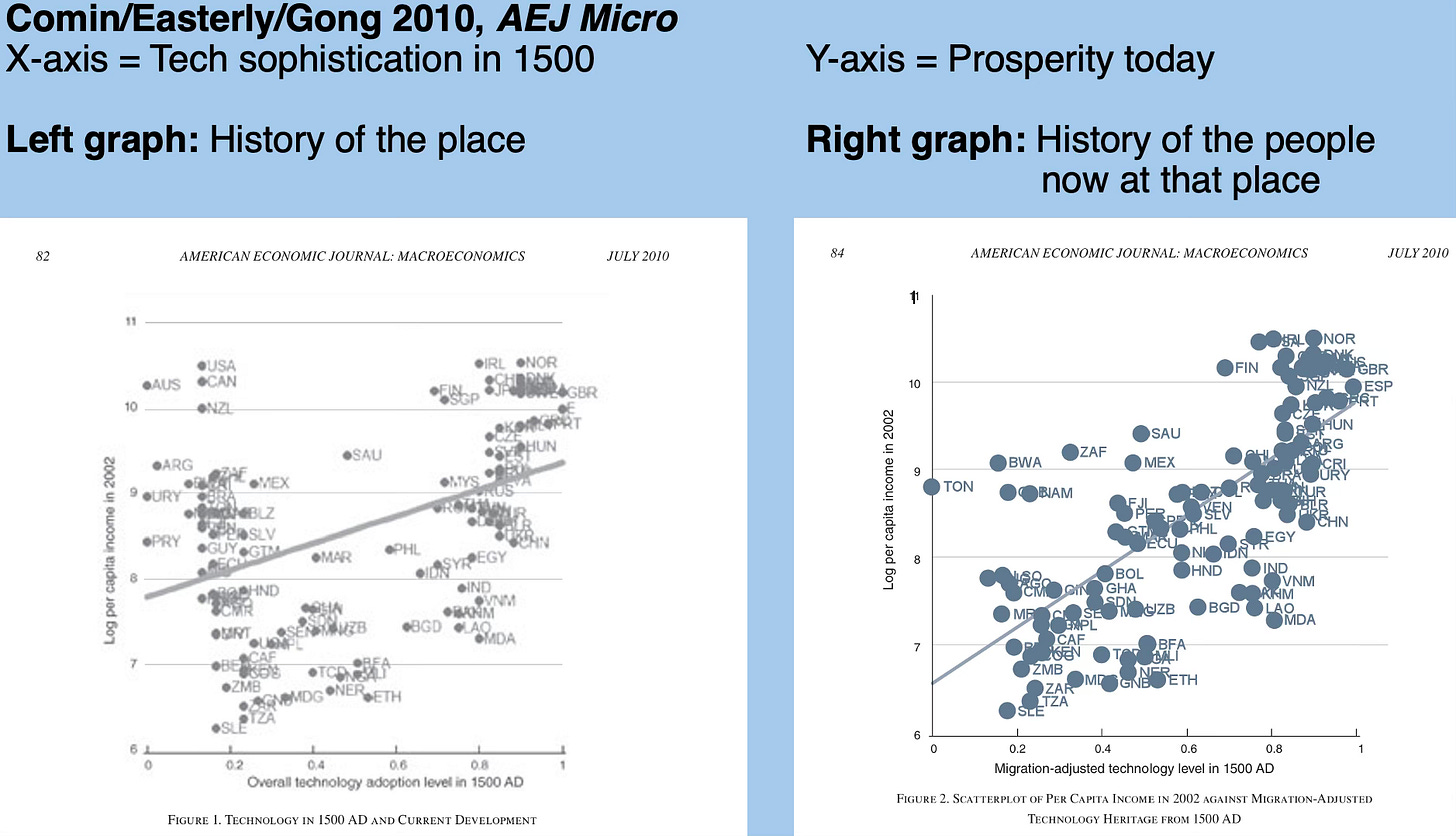

If you look at the graph of the history of the place [Figure 1 from Comin, Easterly, Gong, 2010 American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics] you can see that the USA—Canada—New Zealand—Australia—were not very technologically sophisticated in 1500. So—in a simple regression—you’d expect those places to be poor today. Of course—they’re not, because a lot of Europeans moved there. These neo-Europes as Acemoglu calls them built on the legacy of Europe in 1500, and Europe was at the world’s technological frontier in 1500. Very simple story.

The migration-adjusted measure—illustrated with the graph on the right [Figure 2 in Comin et al.]—fits far better than the migration-unadjusted measure. If you want to understand how rich a place is going to be—you should always be adjusting for migration. If you’re trying to figure out how America’s prospects—or how Europe’s prospects—have changed materially over the last 10 or 20 years—you would want to adjust for migration. Not the only thing you’d want to adjust for—but a good place to start.

These findings mean that there are some errors that some open-borders activists have made along the way. One of them, my GMU colleague Bryan Caplan, is here. He tried to critique the claim of this Putterman-Weil view that the history of peoples matters more than the history of places with a statistical approach of weighting global data by people rather than weighting by countries. In normal statistical analyses of cross-country comparisons, we give each country one observation weight. This is akin to Adam Smith’s idea that we’re studying the wealth of nations—not the wealth of individuals.

His approach is equivalent to giving the People’s Republic of China 50 times the weight of Taiwan and 150 times the weight of Singapore, all of which are Chinese-majority countries. If you’re trying to figure out whether a Chinese society is likely to create a frontier economy, you really have to ask yourself: “Do I think that the PRC gives me 50 times more information than Taiwan? Do I think the PRC gives me 150 times more information than Singapore?” I don’t think so.

But on top of that, Caplan didn’t use the best of the three top predictors of ancestral success. He used the ones created by Putterman and Weil—who were early in the field. We’ve known since 2010 that the Putterman and Weil predictors were weaker than the Year 1500 technological sophistication predictors I showed earlier. Part of the reason we know that is because Putterman and Weil said so in their original paper! The Putterman and Weil predictors were based on how long your ancestors had been using settled agriculture, and how long your ancestors had been living under organized states [Ag History and State History]. So—these are measures that go back thousands of years.

And as I said, we’ve known since 2010 that the best single measure wasn’t agricultural experience or state history experience. It was the one I used earlier—this tech history measure: How was your place doing in 1500?

If you look around at the map of the world today—the map of which places are technologically sophisticated today and which aren’t—not a lot has changed since 1500, once you adjust for migration. We’ve had a lot more change since 4000 BC—5000 BC—2000 BC. We haven’t had that much change since 1500—once you adjust for migration.

And with this ancestral tech history measure, even if I do give China 50 times the weight of Taiwan, and even if I do give China 150 times the weight of Singapore, then tech history is still a good—ancestry-adjusted predictor of prosperity.

Michael Clemens—also my GMU colleague wrote a theoretical paper that got a lot of attention. You’ve all heard that economists get accused of assuming the can opener. This paper assumed that eventually immigrants fully assimilate and stop creating productivity spillovers in the place they move to. The interesting thing is that he really does agree—quite explicitly—that immigrants import new values and that those new values persist across generations. But he assumes that people coming with new values aren’t going to change your country’s productivity.

Here, I think Michael Clemens should talk to Bryan Caplan about whether people with new values will actually change the government. Caplan’s book Myth of the Rational Voter showed exactly how in democracies, politicians actively respond to voters with new values.

And then Alex Nowrasteh—at the Cato Institute—who is also an open-borders activist—he mis-cites the academic literature on interpersonal trust [Kyklos, 2023]. We have studies from the US—Europe—Australia—Canada—showing that about half of ancestral attitudes toward trust get transmitted to their new countries—maybe a third instead of a half. So trust persistence across generations is well-studied, and holds in multiple countries.

Separately, a lot of economists have also run trust experiments in a lab: they look into whether people who say in a survey that you can trust others actually act in more a trusting or more trustworthy way in the lab. At one point, Nowrasteh of Cato lists eight studies by name, saying—”Look—these studies show that people who say you can trust people aren’t any more trusting in experimental games.” So—I went and looked at these eight studies. Four of them actually find that survey trust does predict experimental trust. Four of them find that survey trust predicts experimental trustworthiness.

So Nowrasteh makes sort of a strangely inaccurate claim—published in a peer-reviewed journal. So—I guess maybe the referees were just not checking too much.

Another claim he tried to make [also Kyklos, 2023] is that the long-run persistence of trust is fragile—that there isn’t much of a culture transplant, not much attitude migration. But the paper he cites doesn’t find that at all. It finds the median correlation of 0.3 between home-country trust and trust of descendants. So—this is the paper here— Müller, Benno, Uslaner [Economics Bulletin 2012].

Let me sum up the grand errors of these three open-borders activists:

Caplan doesn’t study the wealth of nations—and to the extent he does, he doesn’t use Comin’s well-respected tech history measure. He needs to fail on both of those counts in order to get his pro-open-borders result.

Clemens should place a Caplan-like faith in the median voter theorem—the view that new voters—with new values—will change government in that direction.

And Nowrasteh should report underlying studies accurately. Further, he should ask his Cato colleague, the great Deirdre McCloskey, about the sin of asterisk worship—which we call the Standard Error of Regressions.

At the same time, immigration restrictionists also make a big mistake. I want to point out that this is something that was brought to my attention—although I don’t recall her precise words—when Amy Wax and I were on a panel together at the Harvard Conservative Conference earlier this year. The immigration restrictionists think that if you stop immigration for a while, then you’re giving the country time to basically digest the cultural food that of all these new people have brought in. That eventually—through a Great Pause of immigration—there will be a wave of assimilation that will eventually last—and that eventually they’ll just become like us.

Instead, we’ve already seen from the attitude migration work that that never happens completely. And more importantly a lot of what we call assimilation is instead a meeting in the middle. We all meet in the middle.

I call this the Spaghetti Theory of Cultural Change. If I were a dumb person doing regressions—I would say—”Whoa—look at how Italian Americans have assimilated to American culture. They eat spaghetti just like the rest of us!” In real life, there’s a lot of meeting in the middle.

I’ve been using that analogy for years. And when I was in Paris to talk about The Culture Transplant with Le Figaro, I saw that there’s a prominent Syrian refugee who’s now a French citizen [Omar Youssef Souleimane] who’s moved to the center-right—because he knows where his friends are. He used a throwaway line once where he says—”Couscous—the national food of the French.” That’s just another example of Spaghetti Theory: we meet in the middle—we change each other.

I picked the easy examples here. Somebody else can go study the hard ones.

Let me return to the policy lesson I made at the start: you can make a nation better in the long run through a smart immigration policy. Notice—this is me trying to talk optimistically. You can make a nation better in the long run through a smart immigration policy. Open-borders activists completely reject this view—because they think that either immigrants assimilate too quickly to bring new—better—values—or that these new values don’t matter at all since government quality doesn’t depend on citizen preferences. They have to give up these possibilities in order to hold their open borders position.

I think you can just bring in better people. It might take a generation or two—but your nation will get better—because they’ll make the new place more like the place they came from. They’ll bring more of those awesome traits that their ancestors had.

My policy advice here is: When you’re running a skill-focused immigration policy—don’t just look at the immigrant’s CV—look at her nation’s CV. Both should deserve some weight if you’re being a rational—evidence-based—person. You can fake a resumé—but you can’t fake your nation’s resumé.

Here are some research questions that I think people could move on—if they’re young and fairly brave [Slide]. I don’t want to overemphasize how brave you have to be to do this. People warned me like—”Oh—don’t do all this IQ stuff before you have tenure—blah—blah—blah—blah—blah.” I did it.

I was glad—glad that I was trained in enough statistical methods that I knew I could go to Wall Street if I really needed to, if academia really did push me out. But I was never really worried. My department treated me exceptionally fairly—and I’m grateful to my colleagues—including Bryan Caplan—for supporting my career.

On ideas for future research, here’s three paper ideas you or other young people could use. I’m glad to talk more about these with folks later.

And I want to close by saying: The first step to believing in diversity is believing that it exists—and believing that it persists.

Full paper that it’s loosely based on here: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/9hgmnrl30l7ptt9e5rz7y/Migration-as-a-Culture-Transplant_Garett_Jones_GMU.pdf?rlkey=4dhiz50p41wshsbwsyvom6g2c&dl=0

The idea that values persist acros generations is critical here. Looking at the neo-Europe examples, its clear that institutions dont just emerge from geography or resources alone but from the people who build them. The spaghetti theory resonates because we do meet in the midlle more often than we fully asimilate. Policy makers should weigh both individual credentials and ancestral outcomes when considering immigration.