Two Years after Dorian Abbot’s Disinvitation, Alumni Conference Strikes a Hopeful Note on MIT’s Progress on Free Speech

I appreciate Dorian Abbot inviting the MIT Free Speech Alliance, of which I serve as Executive Director, to contribute a writeup of our September conference, given that our organization’s founding owes itself directly to Professor Abbot’s disinvitation from delivering a prestigious MIT lecture in 2021. I was on the staff of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression at the time, without the slightest inkling as I watched that drama unfold that it had implications for my own career trajectory.

This was the first conference we’ve held, and one of its operating principles was the desire to represent the views of a number of different institutional stakeholders, setting the tone for how we want to participate in the life of MIT going forward. We have our own ideas on how to improve the climate, but we’re not the only ones, and part of our role in helping the discussion along, as we see it, comes in convening these discussions and elevating the good work others are doing. Fortunately, there was no shortage of such work for us to put on display.

This showed most readily in the two sessions we held whose participants consisted of MIT faculty. First, a panel with MIT philosophy professors Alex Byrne and Brad Skow, alongside Linda Rabieh, a Senior Lecturer in MIT’s Concourse learning community, discussed a promising new initiative the three are spearheading to promote civil discourse at MIT. Their project will feature a number of lectures and discussions open to the public, while also working at promoting better discourse and exchange in the student community, including through Braver Angels-inspired student debates.

The other panel of MIT faculty brought two professors who had served on MIT’s Ad Hoc Working Group on Free Expression, which was assembled following the Abbot controversy to help guide the Institute’s path forward. The working group delivered an extensive report with ten recommendations for improving MIT’s free speech climate. MIT, fortunately, has already met the first recommendation, with the faculty voting to accept the working group’s new Statement on Freedom of Expression and Academic Freedom. MIT’s new president, Sally Kornbluth, followed up the faculty’s work by publicly endorsing the new statement early this year.

It was of great value to hear the perspectives of the two professors, Malick Ghachem and Stephen Graves, who offered a sense of the challenges the heterodox group of faculty faced as they carried out their mandate, a challenge magnified by the decision, made very early on, to be unanimous in its recommendations. Considering the substance and seriousness of the working group’s final product, this was no small task, with no small amount of dissent along the way.

Other sessions on the day turned the focus outward from MIT. One brought in two leaders of the new faculty-led Council on Academic Freedom at Harvard, a coalition of more than 130 faculty united by a common mission of promoting free inquiry, viewpoint diversity, and civil discourse at Harvard. I, like many others, was excited to read of the group’s founding when it was announced earlier this year. The institution-specific, nonpartisan, faculty-led watchdog is a great model, and one I’d love to see replicated at MIT and other institutions. It’s also something that Harvard desperately needs, considering that its numerous lapses and run-ins on free speech and academic freedom netted it the worst score FIRE has ever given in its latest College Free Speech Rankings. (MIT for its part improved modestly in the newest rankings, but still sits just below the middle.)

The MIT Free Speech Alliance is a member of a larger consortium, the Alumni Free Speech Alliance, which has member organizations working to promote free expression at more than 20 institutions around the country. One of our other panels, accordingly, brought together leaders from four AFSA organizations for a discussion of the various methods they use in their outreach and activism, the particular assets they’re able to call on in their work and, relatedly, the unique cultural challenges and pressures facing their institutions.

Our final session paired two Harvard and two MIT students for a freeform discussion. Hearing the students’ individual perspectives on the social pressures that can inhibit a culture of free expression may have made for the day’s most illuminating session, which left me feeling ever luckier to have gone to college 20 years ago, before smartphones and social media so changed its landscape. I’ve also had very few opportunities to hear students discuss their experiences of being in college during the COVID pandemic, and hearing the students discuss their experiences – the isolation and mental health effects, the way it informed their views of university bureaucracies – was enlightening and even heartrending. (The session also highlighted for me just how different the Harvard and MIT student cultures are.)

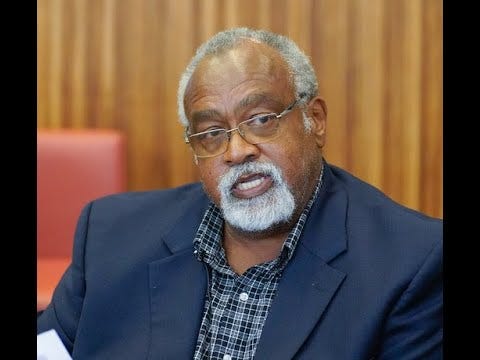

I haven’t even touched the day’s headline act, being the keynote speech delivered by Brown University professor Glenn Loury, in which he argued that the contemporary zeal for antiracism has had real costs for free speech. Given the controversy that has since befallen Ibram X. Kendi and Boston University’s Center for Antiracist Research, and the larger inventory it has prompted even among generally sympathetic observers, his caution seems particularly well-timed.

Among our takeaways from our first conference is a confirmation of the belief that there is a meaningful and serious role for alumni to play in promoting free expression at their institutions. The MIT Free Speech Alliance counts more than 1,000 members, the bulk of them MIT alumni. Representing such a sizable and growing alumni contingent gives us the chance to play a meaningful part in discussions, and gives us the capacity to help convene those discussions as well. We’ll keep doing so, and MIT students, faculty, and leadership can always count on our invitation to take part.

What’s also confirmed by our conference is the knowledge that no single bloc is going to turn around an institution’s culture of free expression. The students, faculty, administration, and alumni will all be needed – and as such we’ll always seek to have all levels of the institution involved in our conferences. I’ve long been of the view that of the blocs operating inside the university, the faculty role is especially vital, and that faculty are ideally positioned to lead on the issue. This is one reason I have come around on statements like the Chicago Principles. They aren’t a panacea – it takes real effort on the ground to give their words meaning – but faculty-authored statements such as these, apart from their clear guidance, act as a way of reasserting the faculty role in university governance.

On the other hand, there are things that only college leaders can do. Once the MIT faculty had approved the new Statement on Freedom of Expression and Academic Freedom, Kornbluth endorsed it in a message to the entire community. This was a real service to MIT. Presidents underestimate just what an effect it can have when they send such messages, but taking clear and decisive stands on free expression can do a surprising amount to inform an institution’s overall culture. (One thing I noted in examining how MIT fared on FIRE’s newest rankings is that it significantly improved on the metric of perceived administrative support for free expression.)

In all, our conference left much to be optimistic about, but also the awareness that there is a lot of work still to do. President Kornbluth has charged members of her senior administration with implementing the recommendations made by the Ad Hoc Working Group; the details on what that looks like remain to be filled in several months later. A new student group we’ve provided with some support, Students for Open Inquiry, is just getting its footing but will hopefully provide another outlet for MIT students interested in meaningful discussion and civil discourse. Progress remains tenuous, and despite MIT’s real improvements on free expression in the past year, its overall climate is still rated by FIRE as “average.” If there’s any descriptor that should offend the sensibilities of its community members, that should be it.

As a final note: Membership in the MIT Free Speech Alliance is free and open to all, whether or not you’re a member of the MIT community! If you’re interested, you can join at this link.

Final final note: Since I authored this post, MIT—like many of its peers—has been beset by campus protests over the Israel/Hamas conflict, some of which were unambiguously disruptive. MFSA offers comment at this link.

Peter, thank you for this report -- the success of MFSA is an inspiration, and a model for others to follow.

How would you describe the difference between Harvard and MIT student cultures?