There is a fork in the road for the future of Cornell University. Cornell must choose between what Jonathan Haidt calls two mutually exclusive telos—the search for truth or social justice activism. The fact that these two teloi are mutually exclusive has been highlighted at Cornell University where the SIPS Diversity and Inclusion Council claims on an official website of the CALS School of Integrative Plant Science (SIPS):

The Council’s vision is for an inclusive SIPS community that flourishes because it values and supports diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice. It recognizes that our institution was founded on and perpetuates various injustices. These include settler colonialism, indigenous dispossession, slavery, racism, classism, sexism, transphobia, homophobia, antisemitism, and ableism.

Does anyone who is reading this now believe that Cornell perpetuates slavery? Does anyone in charge of perpetuating this website care whether this claim is fact or fiction, true or false—a fundamental concern of science at a university? Sadly, as documented in The College Fix and by Constitutional scholar Jonathan Turley, the answer is no.

When the search for truth is subservient to another telos, authoritarianism becomes more likely. As reported in Current Biology, in an 2020 interview with Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg, former President Obama admonished,

If we do not have the capacity to distinguish what’s true from what’s false, then by definition the marketplace of ideas doesn’t work. And by definition our democracy doesn’t work. We are entering into an epistemological crisis.

This is the same sentiment was expressed by Hannah Arendt in The Origins of Totalitarianism:

The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exists.

The search for truth requires open inquiry based on viewpoint diversity, academic freedom, free expression, and constructive disagreement. The current atmosphere of self-censoring at Cornell discourages open inquiry and the search for truth. The system of checks and balances necessary for the search for truth is broken.

Cornell is now dominated by an administration-sanctioned postmodern philosophy based on the idea that there is no objective truth, and that knowledge is a social construct created by those in power to victimize others. A bureaucratically bloated university based on a philosophy that there is no objective truth creates a censorious atmosphere where people would rather self-censor than ask a question that goes against the administration’s post-truth philosophy. Without the disestablishment of the post-truth philosophy from the university, Cornell will not be able to teach students the biological basis of human medicine needed to become physicians, the biological and environmental factors necessary to grow food, or the mathematical principles needed to build bridges and buildings.

Cornell has moved a long way from the telos of truth since Liberty Hyde Bailey, the founder and first dean of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell, wrote in his book Ground-Levels in Democracy:

TO FIND the fact and to know the truth, this is the purpose of the quest of science. If the truth can be applied to the arts of life, the gain is good; but the truth is valuable on its own account, and for the range and reach that it imparts to the mind. As the truth is of itself, as it knows no person and no condition, so is its application impartial and so is its effect on the mind uncompromising.

One never makes the quest with success unless the mind is open at the start. The quest is to find out, always to discover, never to prove a thesis or to demonstrate an assumed position. Herein does this mind differ from that of the advocate who must merely prove a case, or from that of the preacher who must support a dogma, or from that of the politician who must defend a party.

Science cannot be dogmatic, if it is science; it cannot be partisan if its judgment is that of the open mind, seeking. Our policies are largely controlled by the partisan, and by the publicist who endeavors to support his argument. Science is not argumentative: the whole statement of its case is merely the statement of the fact and its significance. There is no taking of sides to truth. The prejudiced mind — the mind that prejudges — is never the scientific mind. Therefore does the science-spirit introduce a modern element into society; and in the end it will reshape our political philosophy.

Science is never partial to any set of facts. It weighs all facts, giving to each its due place and import. It is easy enough to show that the moon exerts powerful influence on the work of the planter if we choose certain coincidences and ignore all the exceptions. This is the political method,—to remember the facts that support our own argument and forget those that have an opposite or a different significance. Most persons in all the daily relations of life see only one side of a situation, which means that they do not see at all but only follow a chosen and blind course, consciously or subconsciously.

Bailey goes on to say, “The science-spirit removes at once the fear of truth and the fear of dogma and the fear of nature. Ignorance is always bondage, and it is the truth that shall make you free.”

Political philosophy now shapes our science, in teaching and in research. STEM has become STEMPA—Science, Technology Engineering, and Math as authorized by Political Activism.

In 2012, nearly a century after Liberty Hyde Bailey wrote the book mentioned above, the California Association of Scholars prepared a report called A Crisis of Competence. It states:

Moral and legal considerations show how the politicization of the classroom damages democratic government and the integrity of public life, but what is most important for the purposes of this report is that politicization has devastating effects on the quality of teaching and research. Put simply, a college education influenced to any significant degree by political activism will inevitably be a greatly inferior education, and the same holds for academic research. Political activism will tend to promote shallow, superficial thinking that falls short of the analytical depth that we expect of the college-educated mind.

The habits of thought that it promotes are in every respect the exact opposite of those we expect a college education to develop. There are many reasons why this must be so.

Results Over Process

First, political activism values politically desirable results more than the process by which conclusions are reached. In education, those priorities must be reversed. The core of a college education is disciplined thinking – thinking that responds to evidence and argument while resisting the lure of what we might wish were the conclusion. Disciplined thinking draws conclusions only after it has weighed the facts against all the plausible explanations of those facts. Strong political beliefs will always threaten to break down that discipline and bend the analysis in a direction that political considerations urgently want it to go.

Stunted Intellectual Curiosity

Second, the fixed quality of a political belief system will stifle intellectual curiosity and freedom of thought when it dominates a classroom. In any worthwhile college education, a student’s mind must have the freedom to think afresh and to follow wherever facts or arguments lead. But this freedom of movement is constrained when the end process of thought has already been fixed in advance by a political agenda. Students will never learn to think for themselves if their thought processes must always conclude by fitting into a particular set of beliefs. Intellectual curiosity is the indispensable prerequisite for analytical power and depth: you cannot reach the latter unless you have the former. Strong political commitments that dominate the classroom will stunt intellectual curiosity, and that can only mean that they will also stunt the analytical power that is a crucial goal of college education.

Action Over Analysis

Third, unlike educational goals, political goals involve specific actions. The need to act in the real world – to choose this course rather than that – makes us simplify a complex of many different factors so that we can decide among a few practical choices. Action is accordingly a blunt instrument compared to analysis. And so while academic teaching and research aim for intellectual depth, political action must tend toward simplification. If action is allowed to rule over analysis, it will always cripple it. To put this point in a different way: political activism tends toward brief slogans (“stop the war!”), while academic thought is likely to produce much more hedged and uncertain statements that weigh pros and cons, neither of which can be wished away. Academic thought will always try to keep in view a variety of factors, not all of which point in the same direction. Analytical knowledge is more complicated than political rallying cries. The latter are the language of the political street, not of the academy.

Lack of Openness to Competing Ideas

Fourth, political activism and academic thought are polar opposites in the way they deal with alternative explanations. When an academic scholar is becoming persuaded that a difficult research problem can be solved in a particular way, he or she knows that the next step must be a careful look at all the plausible alternative explanations, to see if any of them works as well. But this cannot be a perfunctory process: each of those other possibilities must be given the very best shot, and the most sympathetic hearing. Academics know that they must do this if they are to develop new knowledge that will withstand the scrutiny of other experts in the field, and the test of time. This is the essence of the disciplined thinking that they seek to instill in their students.

But political activists tend to have a very different attitude to alternatives to their own convictions: they must be defeated. They do not deserve sympathetic consideration, for they are at best wrong, at worst evil. A genuinely academic thinker must be able to believe for a moment that his own preferred explanation is wrong, so that he can look very hard at the case for other explanations, but that is almost a psychological impossibility for the political or social activist. A recent statement by the Association of American Colleges and Universities correctly stressed the importance in higher education of “new knowledge, different perspectives, competing ideas, and alternative claims to truth.”

The importance of this point would be entirely missed if we saw it simply as requiring a fairminded tolerance of other views. The point goes much deeper. It is precisely by such means that genuinely academic thought proceeds – this must always be one of its core attributes. Academics live by competing ideas and explanations. When activists try to suppress all views but their own, their intolerance is certainly on display, but that is not the point. What really matters is that they are showing us that they are unable to function as academic thinkers, and that they are un-academic in the most fundamental way.

Unwillingness to Rethink

Fifth, when fundamentally new evidence comes to light with respect to any social or political question, another crucial difference emerges. There are two diametrically opposed ways of responding to new evidence. The approach of a disciplined thinker is to set the new evidence in the context of previous explanations of the issue in question to see how the new evidence might change the relative standing of those explanations. Which are advanced, and which are undermined by the new facts? But a person whose mindset is that of a political activist will want to assimilate the new evidence to his or her pre-existing belief system as quickly as possible, and in a way that does not change that system.

Unexpected new evidence is a challenge to rethink, and it presents a most valuable opportunity to do so, but the political activist will be too much the captive of an existing mental framework to take advantage of so welcome an opportunity.

Inconsistency

Sixth, political advocacy and academic inquiry differ markedly with respect to intellectual consistency. In political contexts arguments are routinely deployed according to the needs of the moment, so that, for example, Democratic politicians are for congressional hearings and special prosecutors when Republicans sins are involved, but not when a Democratic administration will be placed at risk; and vice versa. In academic contexts, on the other hand, consistency is indispensable. Arguments must always be principled, never opportunistic, because academic teaching and research aim for results that will stand the test of time, not short-term fixes that serve the immediate political needs of the present situation.

Rejection of the University’s Real Mission

We have left until last the most profound of all differences between academic scholars and political activists. It is one that concerns the very idea of the university, and the reason for its existence. Academia is a kind of repository of the accumulated knowledge, wisdom, and cultural achievements of our society; it preserves, studies, and builds upon that knowledge and those achievements.

Academics are therefore naturally animated by a profound respect for the legacy of our past, and for the storehouse of knowledge and wisdom that it offers us. Their job is in part to pass it on to the next generation, while building on and modifying it.

But all the instincts of radical activists go in the opposite direction. Their natural tendency is to denigrate the past in order to make the case for the sweeping social change that they seek. Accordingly, they don’t look at the past and see accumulated knowledge and wisdom, but instead a story of bigotry, inequality, and racial and sexual prejudice that needs to be swept aside. Political radicals are interested in the utopian future and their never-ending attempts to achieve it, not in the cultural past that must be overcome to get them there.

This is a fundamental difference of temperament, and it will quickly show up in a difference of curricular choices. In studying literature, academic scholars are interested in the great writers who exemplify the imagination and understanding of previous generations at their most powerful, but radical activists ignore these and instead gravitate to those who illustrate the failures of the past. In the study of U.S. history, radical activists focus on those episodes that show the nation’s shortcomings rather than its lasting achievements, avoiding the more realistic and balanced approach of academic scholars. Whenever political activism achieves any substantial presence on campus, the study of our civilization’s great legacy of wisdom and knowledge will be in the hands of people who are in principle hostile to it; they are the last people to whom this task should be entrusted. They will be far too concerned with fighting the battles of the present to think realistically about what can be learned from the past.

When studies show that recent college graduates are alarmingly ignorant of the history and institutions of this country and of the civilization that produced it, we must understand why this has happened. One very important reason is that from the standpoint of political radicals, that knowledge would keep old ideas alive, ideas that they wish to replace, but not by competition in which the stronger ideas prevail. Instead, to force the outcome that they want, they ignore or systematically slight those older ideas by removing material that embodies them from the curriculum. But ignorance of our civilization’s development cannot be considered a choice among different kinds of knowledge; it is simply ignorance. The radical’s choice rests on the assumption that there is no positive storehouse of knowledge that we need to know and build upon, and that assumption amounts to a rejection of the idea of a university.

For all of these reasons, it is beyond any doubt that where radical political activism has substantial influence on college campuses, education will be compromised. Political activism is the antithesis of academic teaching and research. Its habits of thought and behavior are un-academic, even antiacademic. This nation’s universities have been the envy of the world precisely because, unlike those of some other countries, they have been free of politicization. We cannot afford to let them proceed further down a path whose disastrous effects are already well known.

Indeed, Ibram X. Kendi, who has influenced Cornell President Pollack’s policies, wrote in How to Be an Antiracist, “Changing minds is not activism. An activist produces power and policy change, not mental change…Educational and moral suasion is not only a failed strategy. It is a suicidal strategy.”

Kendi’s illiberal strategy is the opposite of liberal enlightenment strategy of educating free people as espoused by John Locke in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding:

it would, methinks, become all men to maintain peace, and the common offices of humanity, and friendship, in the diversity of opinions; since we cannot reasonably expect that any one should readily and obsequiously quit his own opinion, and embrace ours, with a blind resignation to an authority which the understanding of man acknowledges not.

With the current illiberal atmosphere of today’s university, a blind resignation to an authority tends to result in self-censorship.

If the goal of the university is to develop the hearts and minds of people to search for objective truth, free speech, guaranteed by the First Amendment, is fundamental. I have found that a university with a telos of social justice activism results in self-censorship and a stifling of free speech. Free speech is necessary for the search for truth and its transmission to the next generation. The search for truth requires robust discussion and constant questioning of the assumptions, evidence, and analysis that led to the interpretations and conclusions we call objective and truthful knowledge. The ideological and inquisitional attacks on free expression that silenced academics during the House of Un-American Activities Committee and Joseph McCarthy eras were wrong, and the ideological and illiberal attacks on free expression that are silencing academics now is also wrong.

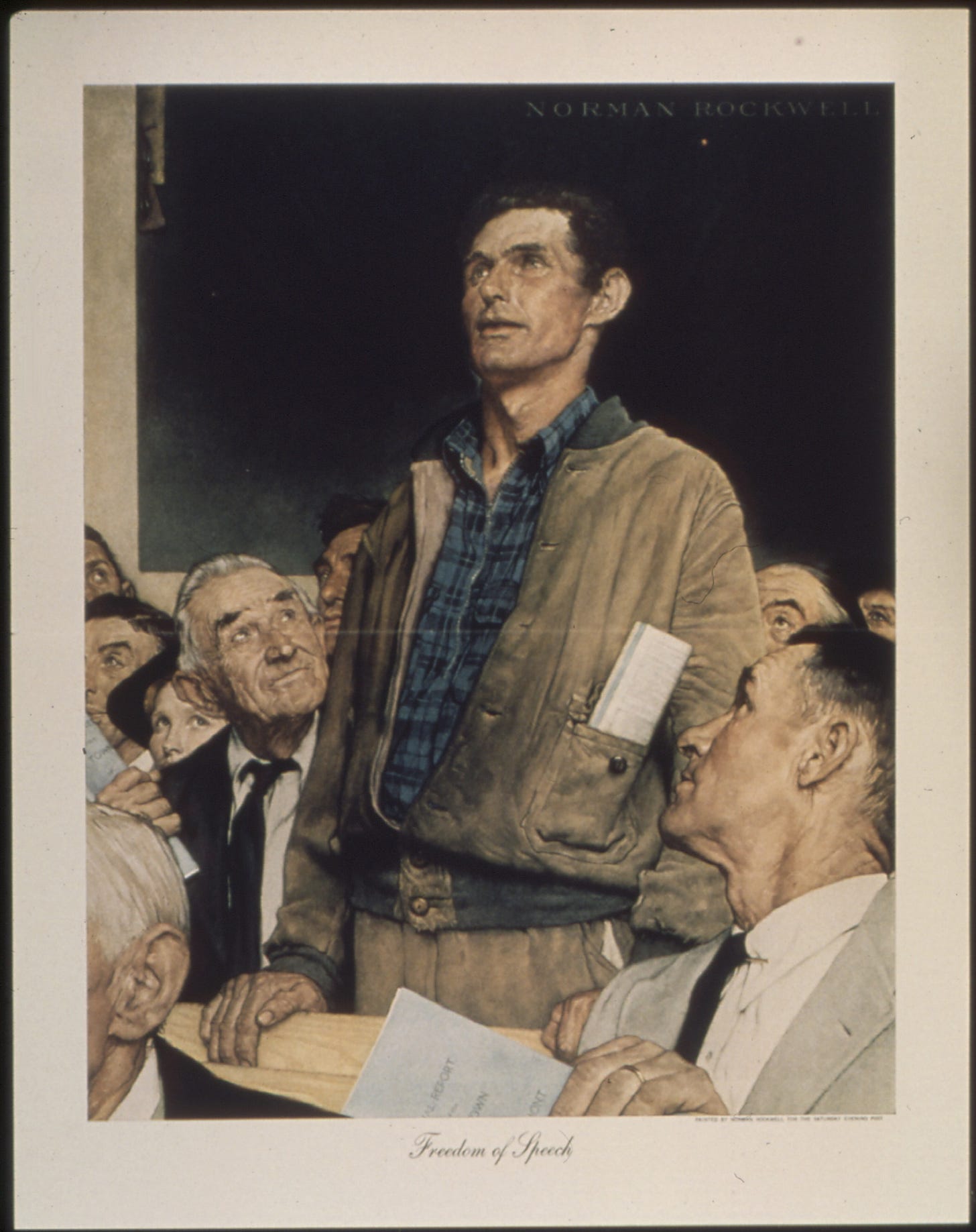

“Freedom of Speech” by Norman Rockwell

According to Nadine Strossen, free speech advocate and former president of the American Civil Liberties Union, it is more productive to “[f]ight hate speech with more speech,” which is consistent with traditional scholarly and social justice values. Take Skokie and the Civil Rights Movement as examples where, in the long run, free speech protected the weak.

In a speech given on September 25, 2012, President Obama spoke of the importance of free speech for minorities.

Americans have fought and died around the globe to protect the right of all people to express their views, even views that we profoundly disagree with. We do not do so because we support hateful speech, but because our founders understood that without such protections, the capacity of each individual to express their own views and practice their own faith may be threatened. We do so because in a diverse society, efforts to restrict speech can quickly become a tool to silence critics and oppress minorities.

Again on September 14, 2015, President Obama spoke inspirationally in favor of free speech and against cancel culture on college campuses.

Free speech, however, is now under attack by political activists at colleges and universities who would rather censor speech than provide reasoned argument stating the assumptions, evidence, and method of analysis for or against an opinion. They see education as a failed strategy and free speech as a weapon of the powerful.

Today’s social justice view of free speech is captured in Catherine A. MacKinnon’s article Weaponizing the First Amendment: An Equality Reading in which she writes:

Once a defense of the powerless, the First Amendment over the last hundred years has mainly become a weapon of the powerful. Starting toward the beginning of the twentieth century, a protection that was once persuasively conceived by dissenters as a shield for radicals, artists and activists, socialists and pacifists, the excluded and the dispossessed, has become a sword for authoritarians, racists and misogynists, Nazis and Klansmen, pornographers, and corporations buying elections in the dark. In public discourse, with which these legal developments are tightly connected, freedom of speech has at the same time gone from a rallying cry for protesters against dominant power to a claimed immunity of those who hold dominant power. Thus weaponized, the First Amendment has morphed from a vaunted entitlement of structurally unequal groups to have their say, to expose their inequality, and to seek equal rights, to a claim by dominant groups to impose and exploit their hegemony.

However, a respect for free speech is necessary to return Cornell University to a telos of truth, and to stimulate critical thinking, nurture intellectual curiosity, and encourage intellectual humility and courage based on disciplined and reasoned analysis of a diversity of data and viewpoints in an atmosphere of open inquiry. To paraphrase Allen Ginsburg in Howl, I have seen the best minds of my generation destroyed by an illiberal social justice movement that equates free speech with weaponization. Social justice activism does have its place at a university, but the type of activism that smothers free speech is an anathema.

Expressing views that do not align with the orthodoxy has its price. As Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in Democracy in America,

the majority draws a formidable circle around thought. Within these limits, the writer is free; but woe to him if he dares to go beyond them. It isn’t that he has to fear an auto-da-fé, but he is exposed to all types of distasteful things and to everyday persecutions.

Consequently, promoting open inquiry required for the search for objective truth at Cornell requires confidence, courage, and mobilization. It also requires gratitude, humility, and humor. A nonhierarchical egalitarian network of independent nonpartisan organizations dedicated to promoting free speech and open inquiry in the pursuit of objective truth at Cornell has emerged. The Freedom and Free Societies Program “encourages Cornellians to think about big questions with the rigor, dispassion, and lack of partisanship that serious academic inquiry requires.” The Cornell Free Speech Alliance: An Independent Alliance of Alumni, Faculty, Students & Staff (CFSA) was created to bring back free speech and viewpoint diversity necessary for the search for objective truth to Cornell. Stimulated by the CFSA, which is composed primarily of Cornell alumni, a student group known as the Cornell Students for Open Inquiry (CSOI) and a faculty group known as the Heterodox Academy Cornell Faculty Campus Community (HxACFCC) have formed.

These groups of Cornell students, faculty, and alumni are being joined by National Organizations concerned with open inquiry, viewpoint diversity, free expression, and academic freedom. These groups include the American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA), the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), the Foundation Against Intolerance & Racism (FAIR), the Alumni Free Speech Alliance (AFSA), the Academic Freedom Alliance, the Steamboat Institute, Heterodox Academy (HxA), Braver Angels, BridgeUSA, and Alumni and Donors Unite (ADU). These groups are coming together with the hope of reinstating the search for objective truth as the telos of Cornell University.

This Spring, the search for objective truth at Cornell University will be nurtured by a presentation of a heterodox viewpoint regarding the pandemic, a robust and civil debate on energy and climate change, and a presentation of the value of constructive disagreement between a Black boogie-woogie piano player and members of the Ku Klux Klan when it comes to fighting racism. There will also be two student debates, one that will involve students campus wide, and another that involves students in the Light and Life class.

On February 20, 2023, Cornell’s Freedom and Free Societies Program will host David B. Shmoys to talk about Cornell’s response to the covid pandemic, and Jay Bhattacharya, who was subjected to a quick and devastating published takedown for his heterodox view on the downsides of covid lockdowns.

On March 15, 2023, Cornell alumni, faculty, students, and staff along with the Light and Life class will host the Steamboat Initiative’s Campus Liberty Tour: Debating the resolution: Climate science compels us to make large and rapid reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. The debate will feature Steven Koonin, undersecretary of energy for science in the U.S. Department of Energy under President Obama and Robert Socolow, Emeritus Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at Princeton University and Co-Director of The Carbon Mitigation Initiative, Princeton Environmental Institute. This will be an Oxford style debate that is aimed at bringing people together to bridge the divide over contentious issues that tend to polarize people. The debate will be live streamed nationwide to the alumni in various Free Speech Alliances as well as faculty in the Heterodox Campus Community Network.

On April 14, 2023, Cornell alumni, faculty, students, and staff along with the Light and Light class will host the Foundation Against Intolerance & Racism’s Daryl Davis to speak about the pro-human approach to fighting racism. According to the pro-human approach, “We should be anti-racism, not anti-racist.”

Daryl Davis will describe the one-on-one conversations he has had with members of the Ku Klux Klan that have led to overcoming ignorance, eliminating fear, changing minds, and eliminating hate. By respectfully listening and speaking freely and honestly, with the goal of understanding, Daryl Davis has been able to bridge differences and promote racial reconciliation. He has persuaded over 200 members to change their minds and leave the Ku Klux Klan. Daryl Davis uses the universal language of music to communicate between people who disagree.

Also in April, the Cornell Students for Open Inquiry will hold a campus-wide debate in conjunction with the College Debates and Discourse Program sponsored by Braver Angels, ACTA, and BridgeUSA. The debate, which will be open to all students, aims at fostering civil discourse on a controversial subject. It will be a collective exercise in thoughtfulness, respect, and help each student to search for objective truth. The debate will be live streamed to the alumni in the Cornell Free Speech Alliance.

In early May, Braver Angels, ACTA and BridgeUSA will also bring the College Debates and Discourse Program to the Light and Life class at Cornell to foster civil discourse through debates that serve as a collective exercise in thoughtfulness, respect, and the search for objective truth.

Together, the people, organizations, and programs described above will demonstrate some of the checks and balances described by Karl Popper in The Open Society and Its Enemies and Jonathan Rauch in The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth that are necessary for the search for truth in a free society in which people are free to think for themselves.

As Jonathan Rauch describes, there are two rules that distinguish the search for truth: The fallibilist rule—each of us may have thinking that is in error; and the empirical rule—no one has final authority on the truth. These two rules necessitate a pluralistic requirement for the search for objective truth—that is, anyone (Cornell administrators included) is welcome to join the search party.

E Pluribus Unum

Randy Wayne

CALS School of Integrative Plant Science

Plant Biology Section

Cornell University

Ithaca, New York 14850 USA

Dear Quarrelsome...the search for truth is very different than claiming to know the truth! The first is Socratic, the second is Platonic!

Dear Trinity654, I think that speaking out and raising objections is far, far less futile than living in a university in which the search for truth is no longer a priority.