We have prepared a compilation of recent articles documenting present-day censorship in science and explaining the mechanism by which censorship in science operates.

Nothing in life is to be feared; it is only to be understood. Now is the time to understand more, so we may fear less. —Marie Sklodowska-Curie

Censorship—the suppression of facts and ideas—is as old as history itself. Censorship has been invoked to protect people's minds from corruption by bad ideas, to shield religious truths from heresy, to protect the feelings of the faithful from blasphemy, and to ensure the safety of the state in time of war.

Suppression of facts and ideas is antithetical to the production of knowledge; yet, from its inception, science has been a target of censorship. Despite the key role science plays in reducing human suffering, providing solutions to pressing problems of humankind, and improving the lives of people worldwide, censorship in science is endemic in even the most advanced democratic societies.

Recently, science journals and publishers have opened a new and disturbing chapter in the history of scientific censorship: the censorship of scientific articles that are alleged to be “harmful” to a particular group or population, a practice that violates the guidelines of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). The practice began with scientific journals retracting articles in response to the demands of online mobs, but has since been codified into policy by various editorial boards and scientific publishers.

Censorship is objectionable on both philosophical and pragmatic grounds. On the philosophical side, the notion that that the public must be protected from dangerous or harmful knowledge is at odds with liberal Enlightenment values, according to which knowledge is power, which the public is capable of using responsibly. On the practical level, by hiding selected facts, censorship distorts our understanding of the world, thereby undermining our ability to solve challenging problems. Censorship also leads to distrust in science. When scientists hide selected facts to promote their political agendas, the public rightfully perceives them as politically motivated agents rather than objective and trustworthy experts.

Despite the long history of scientific censorship and its current prevalence, the mechanisms by which censorship operates, the agents who impose censorship and their motives, and the ultimate costs of censorship have not been systematically investigated. A recent paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) by Cory Clark and 38 co-authors, Prosocial Motives Underlie Scientific Censorship by Scientists: A Perspective and Research Agenda (Clark et al. 2023), takes a stab at this issue. The paper lays out important questions regarding the nature and consequences of censorship and puts out a call for systematic research on the subject.

One of the paper’s co-authors, psychology professor Steve Stewart-Williams, summarizes the evidence for the current wave of scientific censorship and self-censorship, as well as the rise of censorious attitudes among scientists, which motivated the paper:

Increasing numbers of scientists report being sanctioned for conducting politically contentious research.

Retractions of papers have become more and more common over the last decade, and at least some of these appear to have been driven primarily by concerns other than scientific merit. One group of scholars even retracted their own paper, not because it was scientifically flawed, but because it was being cited by conservatives in ways the authors didn’t approve of.

Several lines of research suggest that studies reaching politically unpalatable conclusions may have a harder time negotiating the peer-review process than they would if the conclusions were in the opposite direction. As the paper notes, “When scholars misattribute their rejection of disfavored conclusions to quality concerns that they do not consistently apply, bias and censorship are masquerading as scientific rejection.”

Recent surveys suggest that many academics support censuring or censoring controversial research, with support being strongest among younger scholars.

Unsurprisingly, recent polls also suggest that many academics now self-censor on even mildly controversial topics.

A large number of academics express a willingness to discriminate against conservatives when it comes to hiring, publications, grants, and promotions. Unsurprisingly, conservative scholars are particularly likely to self-censor.

A growing number of journals have explicitly committed to judging scientific papers not just on the quality of the research but also on their (supposed) social or political impact. “In effect,” note Clark et al., “editors are granting themselves vast leeway to censor high-quality research that offends their own moral sensibilities.”

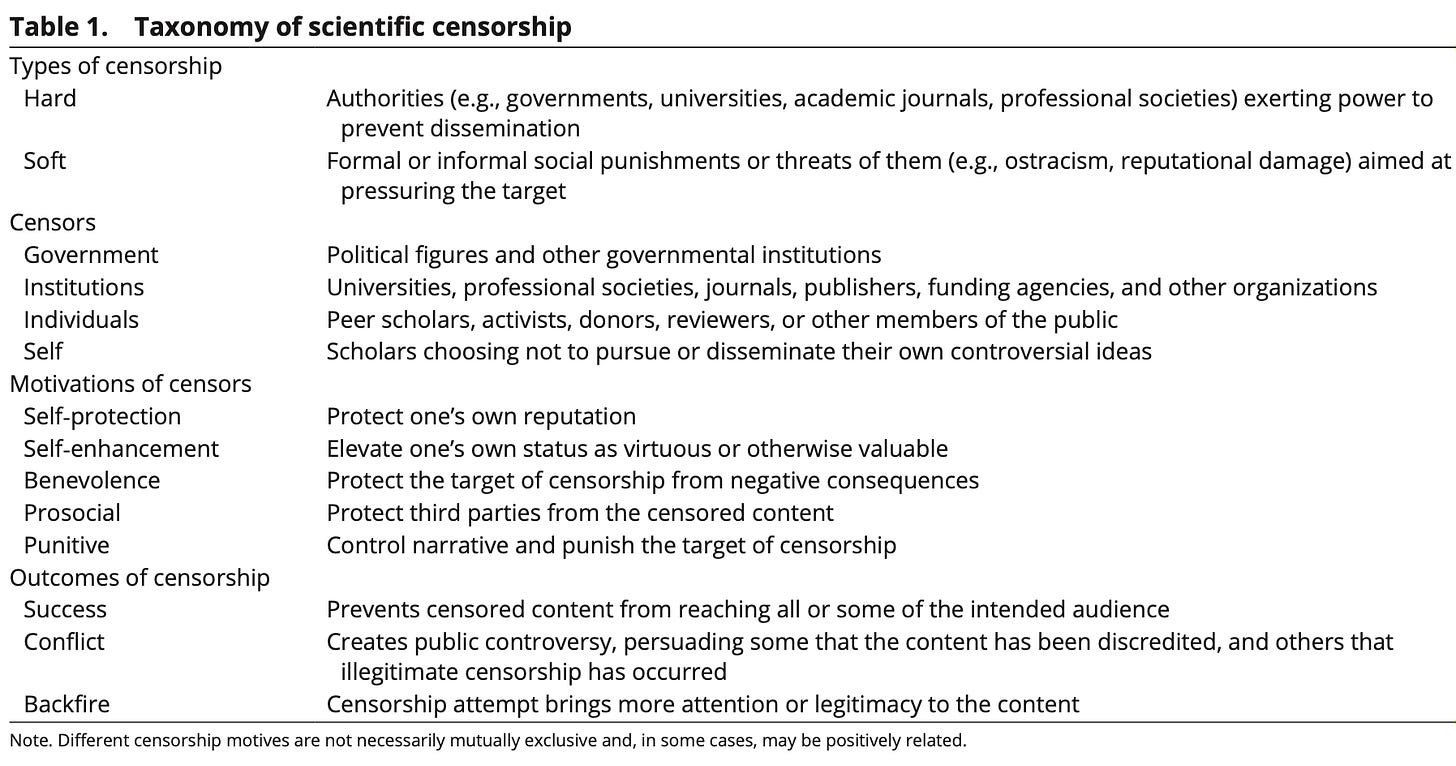

Table 1 of Clark et al. presents the following taxonomy of censorship:

The paper reveals an interesting fact: as the table shows, it is often scientists themselves who are the censors. The paper also explains that the motive for modern scientific censorship is often a pro-social one.

A better understanding of why people engage in censorship and what the downstream costs of censorship are could lead to more effective strategies to combat it. Co-author Distinguished Professor Lee Jussim points out,

University administrators are now well-versed in supposed threats to social justice; far fewer know much about or have deep commitments to academic freedom. Consequently, the immediate and downstream costs of censorship are rarely considered or weighed against the supposed benefits of not causing offense. No wonder we have seen a rising tide of scientific censorship.

Lead author Cory Clark expresses hope that the paper

will raise the standards of our science leaders and decision-makers who aim to obstruct science based on their personal moral intuitions. At minimum, they should be held to the same standards as the rest of us who strive to create and disseminate science, and make their case with data.

Motivated by publication of this foundational paper (Clark et al. 2023), we have compiled a virtual collection of scientific papers, viewpoints, and op-eds that document the modern rise of censorship in science. Our list is most likely incomplete and we encourage readers to add relevant references in the comments.

The Virtual Collection

The foundational paper that motivated this collection:

Clark et al, Prosocial Motives Underlie Scientific Censorship by Scientists: A Perspective and Research Agenda, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120 e2301642120, 2023.

Op-eds and blogs discussing the findings and limitations of Clark et al.:

Musa al-Gharbi and Cory Clark, Science Has a Censorship Problem, The Chronicle of Higher Education, 2023.

Musa al-Gharbi and Nicole Barbaro, Measuring Censorship Is Hard, and Stopping It May Be Harder, Inside Higher Ed, 2023.

Musa al-Gharbi, Free Speech Advocates Are Often Hypocrites. This Doesn't Make the Cause Less Important. Reason, 2023.

Cory Clark and Musa al-Gharbi with Andrew Revkin, Can Any Good Come When Scientists Censor Science, Including Their Own? Sustain What? (Watch on YouTube), 2023.

Steve Stewart-Williams, Scientists Censoring Science, The Nature-Nurture-Nietzsche Newsletter, 2023.

Lee Jussim, Scientists Censoring Science, Unsafe Science, 2023.

Marcel Kuntz, La censure en science et ses motivations idéologiques, Factuel (in French), 2023.

Jerry Coyne, Censorship in Science: A New Paper and Analysis, Why Evolution Is True, 2023.

Johanna Alonso, Worries of Harm Lead to Scientific Censorship, Inside Higher Ed, 2023.

Alan Jacobs, Self-Censorship and Don Quixote, The Hedgehog Review, 2023.

Matthew Giffin, Scientists Urge Clearer Publishing Standards to Reduce Bias, Regain Public Trust, The College Fix, 2023.

The main criticisms of Clark et al. (2023) refer not to what the paper said but to what it omitted. Due to page limitations of the journal, some important aspects of censorship simply could not receive full attention. With regard to the above pieces,

Kuntz (2023) found it odd that the paper did not mention the main ideological driver of present-day censorship: Critical Social Justice (CSJ), sometimes called Wokeism. Indeed, much of today’s pro-socially motivated censorship springs from the CSJ movement.

Alonso (2023) quotes an ethicist, who claims, “There are thousands and thousands of examples of scientific articles published in good scientific journals that lead to real tangible harm.” The claim, asserted without evidence, exemplifies, as noted by Clark et al. (2023), that harm is assumed rather than demonstrated by credible research data. At the same time, the purported benefits of censorship have yet to be illustrated.

Jacobs (2023) questions the concept of self-censorship, characterizing it instead as an act of prudential judgement.

Giffin (2023) highlights the need for credible evidence of harms. Quoting Clark and al-Gharbi,

“What’s new is that journals are now explicitly endorsing moral concerns as legitimate reasons to suppress science,” [Clark et al.] wrote.

In their paper, Al-Gharbi, Clark and their co-authors suggested trying to scientifically measure or predict potential dangers that could be caused by the publication of research findings rather than “relying on the often arbitrary intuitions and authority of small and unrepresentative editorial boards of journals.”

Coyne (2023) writes:

The article lacks tangible examples of how odious this kind of censorship can be. Examples really hit home, especially when you see how hypocritical and sneaky authors and journals can be, even when acting pro-socially.

We agree and present, below, a compilation of papers that enumerate such odious examples.

S.T. Stevens, L. Jussim, N. Honeycutt, Scholarship Suppression: Theoretical Perspectives and Emerging Trends, Societies 10 82, 2020.

The paper describes examples of present-day censorship, comparing and contrasting them with historical examples. The authors emphasize the role activists and social media play in censorship, a topic not covered in depth by Clark et al. (2023). Stevens et al. (2020) introduces the concept of the outrage mob, namely,

A group or crowd of people whose goal is to sanction or punish the individual, individuals, or organization they consider responsible for something that offends, insults, or affronts their beliefs, values, or feelings. This group or crowd demonstrates a flagrant disinterest in any further explanation from the target or targets and attempts to carry out punishment often by enlisting authorities with the power to level sanctions on the target or targets.

Stevens et al. (2020) also makes an important point regarding the role of complacent academic leadership:

Although outrage mobs often trigger the punishment process, in Western democracies, mobs no longer actually burn witches at stakes. For most punishment to occur in academia, some authority has to agree to implement the mob’s punishment. That is, mobs do not get academics fired; it is high level administrators, such as deans, provosts, and university presidents that implement firings. Mobs do not get papers retracted; that is the decision of editors and editorial boards. Thus, the key turning point in whether an academic outrage mob is effective at punishing an academic for their ideas is usually the action of authorities.

L. Jussim, N. Honeycutt, A. Careem, N. Bork, D. Finkelstein, S. Yanovsky, J. Finkelstein, The New Book Burners: Academic Tribalism, Book chapter in The Tribal Mind: The Psychology of Collectivism, Schrödinger Press, forthcoming. Preprint available here.

From the introduction:

We use the term “book burning” as did Bradbury: both descriptively and metaphorically to include burning of actual books, but, especially within academia, to calls to retract, remove, and memory-hole published papers. In the present chapter, we focus on factors that have undergirded book burning for thousands of years: a sense of righteous victimization and a desire by the book burners to impose their values and norms on others.

The authors explain that cognitive rigidity and censoriousness are manifestations of tribalism (or political sectarianism) and authoritarianism. They also describe examples of “book burning [of] peer reviewed articles”—retractions of published papers in response to outrage campaigns—such as Gilley's viewpoint essay in Third World Quarterly, Hudlicky's retrospective essay in Angewandte Chemie, Gliske's paper on a new theory of gender dysphoria in eNeuro, and a block-retraction of five papers from Perspectives on Psychological Science.

Several studies have investigated the psychology of censorship, e.g., what motivates censorious attitudes:

C.J. Clark, M. Graso, I. Redstone, P.E. Tetlock, Harm Hypervigilance in Public Reactions to Scientific Evidence, Psych. Science 34 834, 2023.

This paper demonstrates that people often overestimate harmful, and underestimate helpful, reactions to science and that these tendencies are associated with greater support for scientific censorship. The paper also presents consistent evidence for motivated confusion:

Those more offended by scientific findings reported greater difficulty understanding them. This finding relates to the philosophical concept of “dismissive incomprehension,” the tendency to deflect dissonant claims by characterizing them as incomprehensible.

C.J. Clark, B. Winegard, Sex and the Academy, Quillette, 2023.

This paper presents statistics revealing interesting differences in censorious attitudes among the two sexes.

A.I. Krylov, G. Frenking, P.M.W. Gill, Royal Society of Chemistry Provides Guidelines for Censorship to its Editors, Chemistry International 44 32, 2022.

This short article calls attention to censorship guidelines in chemistry publishing, which were recently introduced by the Royal Society of Chemistry. The guidelines emphasize that “it is the perception of the recipient that determines offense, regardless of author intent" and so broadly define offensive content (e.g., any content “likely to be upsetting, insulting or objectionable to some or most people”) that nearly any paper could be censored. This policy is still in place.

A.I. Krylov, J. Tanzman, Critical Social Justice Subverts Scientific Publishing, Eur. Review 31 527, 2023.

This paper, published in the special collection Perils for Science in Democracies and Authoritarian Countries, discusses censorship in STEM publishing in a historical context and explicitly points to Critical Social Justice as the main ideological driving force behind present-day censorship. The paper presents examples of suppression of research findings and raises an alarm about recent proposals to suppress “harmful” research at the funding stage.

The corruption of science and education by Critical Social Justice is also discussed in other papers in the collection, for example, in The Notion of Truth in Sciences and Medicine, Why it Matters and Why We Must Defend It by Bikfalvi and The Universalism of Mathematics and its Detractors: Relativism and Radical Equalitarianism Threaten STEM Disciplines in the US by Klainerman.

J. Rauch, Nature Human Misbehavior: Politicized Science is Neither Science nor Progress, FIRE, 2022.

Jonathan Rauch, author of the seminal books Kindly Inquisitors: The New Attacks on Free Thought and The Constitution of Knowledge, takes to task an editorial published in Nature Human Behavior (NHB), which announced that the NHB editorial board will censor research that they consider harmful. The NHB editorial is a censorship manifesto from its opening line, “Although academic freedom is fundamental, it is not unbounded,” to its proposed roadmap of how censorship will be implemented:

There is a fine balance between academic freedom and the protection of the dignity and rights of individuals and human groups. We commit to using this guidance cautiously and judiciously, consulting with ethics experts and advocacy groups where needed.

Rauch takes apart NHB’s arguments and provides compelling examples of research that could have easily been censored under NHB’s new policy, but which led to important breakthroughs in our understanding of human nature and ultimately advanced important social causes.

A related in-depth critique of the NHB manifesto The Fall of Nature has been published by Bo Winegard in Quillette.

G. Geher, Discovering Natural Selection Was Like “Confessing a Murder”, Psychology Today, 2022.

Geher discusses the harms of self-censorship using a historic example: Darwin's hesitancy to publish on the evolution of life because of the anticipated impact of his findings. As he wrote to the botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker: “It is as if one were confessing to a murder.” Darwin’s discomfort was so great that he reported vomiting regularly, thinking about the implications of the theory of evolution on the perceived special place of Homo Sapiens among other species.

Geher writes “Darwin's ultimate decision to publish about evolution shaped our understanding of the world profoundly” and argues that holding onto critical findings is doing humanity a disservice.

Not all research findings are going to be popular. And not all scientific ideas are going to be loved by all. But publishing ideas and findings that might cut against the grain, at the end of the day, helps us better understand the nature of the world. And that, as I see it, is kind of the point of science. Right?

Yes, indeed — we agree!

Several articles dissect recent ideologically motivated retractions and self-retractions—these are among the odious examples of censorship that Jerry Coyne alluded to in his critique.

J. Savolainen, Unequal Treatment Under the Flaw: Race, Crime & Retractions, Current Psychology, 2023.

J. Savolainen, If The Findings Detract, You Must Retract, Quillette, 2023 (Cesario’s case).

B. Gilley, The Case for Colonialism: A Response to My Critics, Academic Questions, 2022.

T. Hill, Academic Activists Send a Published Paper down the Memory Hall, Quillette, 2018 (the Hill and Tabachnikov case).

A. Marcus, Journal Retracts Paper on Gender Dysphoria After 900 Critics Petition, Retraction Watch, 2020 (Gliske’s case).

L. Krauss, An Astronomer Cancels His Own Research – Because the Results Weren’t Popular, Quillette, 2021 (Kormendy’s case; see also here).

T. Reynholds, Retracting a Controversial Paper Won’t Help Female Scientists, Quillette, 2020 (AlShebli’s case; see also here).

C. Wright, Anatomy of a Scientific Scandal, City Journal, 2023.

M. Bailey, My Research on Gender Dysphoria Was Censored. But I Won’t Be. The Free Press, 2023 (the Diaz and Bailey case).

L. McMillan, Canadian Medical Association Journal Yields to External Religious Pressure, Censors Published Letter, guest post on Why Evolution Is True, 2023 (see also here).

Several papers discussed the case of the late Tomas Hudlicky, whose peer-reviewed and accepted paper was removed, without a retraction notice, from the journal’s website and who was subjected to relentless harassment and ostracism:

L.K. Sydnes, The Hudlicky Case—A Reflection on the Current State of Affairs, Chemistry International 43 42, 2021.

A.I. Krylov, J.S. Tanzman, G. Frenking, and P.M.W. Gill, Scientists Must Resist Cancel Culture, Nachrichten aus der Chemie 70 12, 2022.

U. Deichmann, Science, Race, and Scientific Truth, Past and Present, Eur. Review 31 459, 2023.

More examples of ideologically motivated suppression of scientific facts, from the field of biology, are discussed by Jerry Coyne and Luana Maroja in The Ideological Subversion of Biology, published in the Skeptical Inquirer. Their article also warns of the disastrous consequences of suppression and ideological distortion of knowledge in biology.

As the examples above reveal, cases of censorship in science are often reported in non-academic outlets. In our experience (in particular with Clark et al. (2023) and Abbot et al. (2023)), however, even when such articles reflect rigorous research and analysis and are written by authors with academic credentials, citing them in a scientific paper is met with resistance from reviewers and editors. Whether such resistance reflects legitimate concern about the rigor of the scholarship or is itself ideologically motivated censorship is often unclear.

Because editors often mask ideological censorship as methodological criticism, it is often difficult to differentiate between the two. As Clark et al. (2023) point out:

Contemporary scientific censorship is typically the soft variety, which can be difficult to distinguish from legitimate scientific rejection. Science advances through robust criticism and rejection of ideas that have been scrutinized and contradicted by evidence. Papers rejected for failing to meet conventional standards have not been censored. However, many criteria that influence scientific decision-making, including novelty, interest, “fit,” and even quality are often ambiguous and subjective, which enables scholars to exaggerate flaws or make unreasonable demands to justify rejection of unpalatable findings.

Although it is often difficult to prove that a paper purportedly rejected for methodological shortcomings was actually rejected on ideological grounds, in some cases the real reason for rejection is too obvious to conceal. We illustrate this with two examples, below.

C. Reichhardt, A. Small, C. Nisoli, C. Reichhardt, Resistance to Critiques in the Academic Literature: An Example from Physics Education Research, Eur. Review 31 547, 2023.

The authors present a rebuttal of a paper recently published in the physics education journal Physical Review—Physics Education Research. The paper, which is titled Observing Whiteness in Introductory Physics: A Case Study, arguably sounds more like a hoax than an actual paper with content relevant to physics education. But the rebuttal treats the paper seriously and offers a substantive, professional, and detailed critique. The rebuttal, which was submitted to the same journal as the original paper, was rejected by the editors. The main reason cited for the rejection was that the rebuttal was “framed from the perspective of a research paradigm that is different from the one of the research being critiqued”—indeed, the authors used scientific methods to debunk a postmodernist paper. The communication between the authors and the journal revealed the true nature of rejection.

The second example is the story of how a paper with the seemingly mundane title In Defense of Merit in Science (Abbot et al. 2023) wound up being published in the Journal of Controversial Ideas. The story is narrated by Coyne and Krylov in The 'Hurtful' Idea of Scientific Merit, an op-ed published in the Wall Street Journal (for a non-paywalled transcript see Our Wall Street Journal Op-ed: Free at Last!, published by Coyne on Why Evolution is True).

The conversation about censorship would not in be complete without noting that the rise of academic censorship, retractions, and self-retractions in response to mob outrage campaigns is part of a larger social phenomenon: Cancel Culture, which, in The Cancelling of the American Mind, Greg Lukianoff and Rikki Schlott define as,

The uptick beginning around 2014, and accelerating in 2017 and after, of campaigns to get people fired, disinvited, deplatformed, or otherwise punished for speech that is—or would be—protected by First Amendment standards and the climate of fear and conformity that has resulted from this uptick.

The book documents the rise of cancellation campaigns on campuses, which have contributed to the current climate of fear and self-censorship in social and academic settings. Statistics illustrating the extent of Cancel Culture are also given in the short essay by Lukianoff, The New Red Scare Taking over America's College Campuses (FIRE, 2023).

In Closing

Clark et al. conclude:

We have more questions than we have answers. Although many members of our research team are concerned about growing censoriousness in science, there is great diversity of opinion among us about whether and where scholars should “draw the line” on inquiry. We all agree, however, that the scientific community would be better situated to resolve these debates, if—instead of arguing in circles based on conflicting intuitions—we spent our time collecting relevant data. It is possible that there are some instances in which censoring science promotes the greater good, but we cannot know that until we have better science on scientific censorship.

We too hope that the subject of censorship will receive the scientific attention it deserves. We hope that future studies will shed light on the harms of censorship and that a deeper understanding of how censorship operates will help to restore freedom of inquiry in science.

We began our introduction to this virtual collection with the words of Marie Sklodowska-Curie. We conclude with the words of Plato:

We can easily forgive a child who is afraid of the dark; the real tragedy of life is when men are afraid of the light.

References:

D. Abbot, A. Bikfalvi, A.L. Bleske-Rechek, W. Bodmer, P. Boghossian, C.M. Carvalho, J. Ciccolini, J.A. Coyne, J. Gauss, P.M.W. Gill, S. Jitomirskaya, L. Jussim, A.I. Krylov, G.C. Loury, P. Nayna Schwerdtle, L. Maroja, J.H. McWhorter, S. Moosavi, J. Pearl, M.A. Quintanilla-Tornel, H.F. Schaefer III, P.R. Schreiner, P. Schwerdtfeger, D. Shechtman, M. Schifman, J. Tanzman, B.L. Trout, A. Warshel, and J.D. West, In Defense of Merit In Science, The Journal of Controversial Ideas 3 1, 2023.

M. al-Gharbi, Free Speech Advocates Are Often Hypocrites. This Doesn't Make the Cause Less Important. Reason, 2023.

M. al-Gharbi and Nicole Barbaro, Measuring Censorship Is Hard, and Stopping It May Be Harder, Inside Higher Ed, 2023.

M. al-Gharbi and Cory Clark, Science Has a Censorship Problem, The Chronicle of Higher Education, 2023.

J. Alonso, Worries of Harm Lead to Scientific Censorship, Inside Higher Ed, 2023.

M. Bailey, My Research on Gender Dysphoria Was Censored. But I Won’t Be. The Free Press, 2023.

C. Clark, M. al-Gharbi, and A. Revkin, Can Any Good Come When Scientists Censor Science, Including Their Own? Sustain What? (watch on YouTube), 2023.

C.J. Clark, L. Jussim, K. Frey, S.T. Stevens, M. al-Gharbi, K. Aquino, J.M. Bailey, N. Barbaro, R.F. Baumeister, A. Bleske-Rechek, D. Buss, S. Ceci, M. Del Giudice, P.H. Ditto, J.P. Forgas, D.C. Geary, G. Geher, S. Haider, N. Honeycutt, H. Joshi, A.I. Krylov, E. Loftus, G. Loury, L. Lu, M. Macy, C.C. Martin, J. McWhorter, G. Miller, P. Paresky, S. Pinker, W. Reily, C. Salmon, S. Stewart-Williams, P.E. Tetlock, W. Williams, A.E. Wilson, B.M. Winegard, G. Yancey, and W. von Hippel, Prosocial Motives Underlie Scientific Censorship by Scientists: A Perspective and Research Agenda, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120 e2301642120, 2023.

C.J. Clark, M. Graso, I. Redstone, P.E. Tetlock, Harm Hypervigilance in Public Reactions to Scientific Evidence, Psych. Science 34 834, 2023.

C.J. Clark, B. Winegard, Sex and the Academy, Quillette, 2023.

J. Coyne, Censorship in Science: A New Paper and Analysis, Why Evolution Is True, 2023.

J. Coyne and A. Krylov, The 'Hurtful' Idea of Scientific Merit, The Wall Street Journal, 2023.

J. Coyne and L. Maroja, The Ideological Subversion of Biology, Skeptical Inquirer, 2023.

U. Deichmann, Science, Race, and Scientific Truth, Past and Present, Eur. Review 31 459, 2023.

G. Geher, Discovering Natural Selection Was Like “Confessing a Murder”, Psychology Today, 2022.

M. Giffin, Scientists Urge Clearer Publishing Standards to Reduce Bias, Regain Public Trust, The College Fix, 2023.

B. Gilley, The Case for Colonialism: A Response to My Critics, Academic Questions, 2022.

T. Hill, Academic Activists Send a Published Paper down the Memory Hall, Quillette, 2018.

A. Jacobs, Self-Censorship and Don Quixote, The Hedgehog Review, 2023.

L. Jussim, Scientists Censoring Science, Unsafe Science, 2023.

L. Jussim, N. Honeycutt, A. Careem, N. Bork, D. Finkelstein, S. Yanovsky, J. Finkelstein, The New Book Burners: Academic Tribalism, Book chapter in The Tribal Mind: The Psychology of Collectivism, Schrödinger Press, forthcoming. Preprint available here.

A. Kellerbauer, Perils for Science in Democracies and Authoritarian Countries: Editorial, Eur. Review 31 423, 2023.

L. Krauss, An Astronomer Cancels His Own Research – Because the Results Weren’t Popular, Quillette, 2021; see also here.

A.I. Krylov, G. Frenking, P.M.W. Gill, Royal Society of Chemistry Provides Guidelines for Censorship to its Editors, Chemistry International 44 32, 2022.

A.I. Krylov, J.S. Tanzman, G. Frenking, and P.M.W. Gill, Scientists Must Resist Cancel Culture, Nachrichten aus der Chemie 70 12, 2022.

M. Kuntz, La censure en science et ses motivations idéologiques, Factuel (in French), 2023.

G. Lukianoff, The New Red Scare Taking over America's College Campuses, FIRE, 2023.

G. Lukianoff and R. Schlott, The Cancelling of the American Mind, Simon and Schuster, 2023.

A. Marcus, Journal Retracts Paper on Gender Dysphoria After 900 Critics Petition, Retraction Watch, 2020.

L. McMillan, Canadian Medical Association Journal yields to external religious pressure, censors published letter, guest post on Why Evolution Is True, 2023 (see also here).

J. Rauch, Nature Human Misbehavior: Politicized Science Is Neither Science nor Progress, FIRE, 2022.

T. Reynholds, Retracting a Controversial Paper Won’t Help Female Scientists, Quillette, 2020 (see also here).

S.T. Stevens, L. Jussim, N. Honeycutt, Scholarship Suppression: Theoretical Perspectives and Emerging Trends, Societies 10 82, 2020.

S. Stewart-Williams, Scientists Censoring Science, The Nature-Nurture-Nietzsche Newsletter, 2023.

J. Savolainen, Unequal Treatment Under the Flaw: Race, Crime & Retractions, Current Psychology, 2023.

J. Savolainen, If The Findings Detract, You Must Retract, Quillette, 2023.

L.K. Sydnes, The Hudlicky Case—A Reflection on the Current State of Affairs, Chemistry International 43 42, 2021.

B. Winegard, The Fall of Nature, Quillette, 2022.

C. Wright, Anatomy of a Scientific Scandal, City Journal, 2023.

Censorship only helps tyrants.

In my 60 yearlong career as a scientist there has rarely been a period in which powerful people who were inconvenienced by my findings were not trying to censor me., often by trying to destroy my livelihood and sometimes successfully.