Pre-college math education in the US could be much more advanced and engaging than the dry, dull, dumbed-down status quo. This essay proposes a major revamp of curriculum, integration of math with coding, certification of competency, grouping by ability, and more parental choice. It also exposes the main obstacles: cultural squeamishness about math, schools’ bureaucratic inertia, and a misguided sense of social justice. While the obstacles currently dominate the US as a whole, some schools have enough autonomy to experiment if they want. I think they and their students would be thrilled by the results. Families would vote with their feet to join, which in turn would help galvanize broader change.

I start with a bold claim: Every high school graduate in the US should be familiar with core elements of calculus, linear algebra, and probability theory. They should be able to demonstrate this familiarity by enlisting AI helpers to write useful code applying these concepts and by explaining in their own words how this code works.

Why? Because this is both immensely useful and practically feasible. Calculus, linear algebra and probability theory are the core tools of machine learning and vital to research in most tech-related fields. Familiarity lets us glimpse how AI thinks and facilitates communication with it. And it’s not that hard to become familiar, thanks in part to advances in AI.

We can’t get there through minor tweaks in current elementary and secondary school math curricula. The whole approach needs to be revamped. The current path is too slow, too cluttered, and too boring. It focuses way too much on memorization and computational skills. It focuses far too little on understanding the broad reach of a few core principles and developing practical intuition for them. It draws too few connections with real-world puzzles and divorces problem-solving from coding.

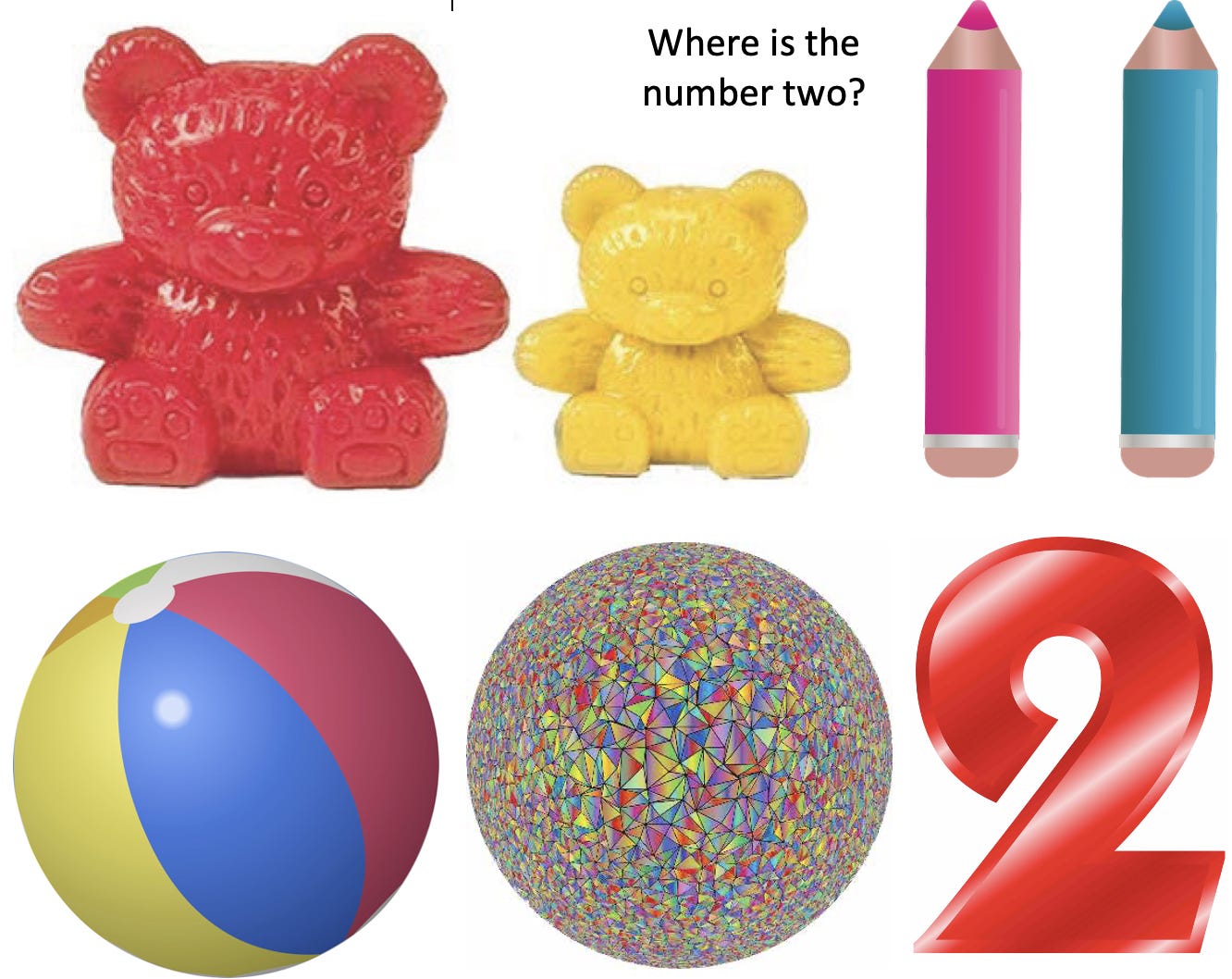

The easiest way to improve math education is to treat it as a progression through types of numbers. The hardest level is the foundation. Show me the number two. If you point to “2” or “II”, that’s wrong; those are symbols for two and not the number itself. If you point to two counting bears or balls or pencils or balls or counting bears, that mixes the two with something else. Two is a particular quantity abstracted from every other quality. And don’t expect much help from the formal mathematical definition: the set consisting of an empty set and a set that contains the empty set. The only way to intuitively grasp two is to start counting at one and learn that two is one more.

That’s true more generally. To teach a math concept efficiently, figure out a neat way to convey it intuitively, demonstrate it, and have students practice with a few examples to help it sink in. The less clutter, the fewer rules to memorize, the better. Consider the Pythagorean theorem, by any name one prefers to call it. Out of the 300+ ways to prove it, here is one of the best, since it quickly makes clear both what it is and why it works. Indeed, it makes the theorem seem obvious. And that’s the goal: not to teach complicated things, but to make them look simple.

Critics may object that the theorem is only an introduction to what really matters: learning to square a and b and take the square root of their sum. Once that was true, since humans needed to to compute things on their own. But now we have electronic computers to do the pesky stuff for us, far quicker and more reliably. No point wasting much mental power on that; let’s concentrate on thoughtful application. Is it easier to throw a ball 20 yards straight downfield or 15 yards downfield and 10 yards to the left? What are the dimensions of a computer screen with a 24” diagonal and 16:9 aspect ratio? Learning to set up those problems is far more important than manually computing the answer.

Seven-By-Seven Math Curriculum

There are many types of numbers and it is easiest to learn one at a time. My proposed K-12 math curriculum organizes that into seven levels, with seven core topics in each level. Here is an outline:

How many? (whole numbers)

Counting

Addition

Subtraction

Multiplication

Base 10 notation

Division

Computer math (binary system)

How far? (negative, fractional, and real numbers)

Number line with positive and negative numbers

Subtraction as addition of negative numbers

Commutative, associative, and distributive rules

Fractions

Decimals

Powers

Infinite series

Geometry (numbers related to shapes)

Points and lines

Rectangles

Triangles

Graphs

Polygons

Circles

3D Figures

Algebra (variable numbers)

Arithmetic with letters

Linear equations

Simultaneous linear equations

Quadratic equations

Complex numbers

Polynomials

Polar coordinates

Calculus (infinitesimal numbers)

Notion of derivative

Integrals

Slopes

Slopes of slopes

Infinite series

Logarithms and exponentials

Circle functions

Linear Algebra (arrays of numbers)

Vectors

Matrices

Inversion

Multivariate regression

Principal components

Partial derivatives

Neural networks

Probability (random numbers)

Randomness

Counting rules

Binary outcomes

Multiple outcomes

Expectations

Sampling

Bayes’ rule

The biggest reordering from the status quo is the direct jump from algebra to calculus. The intermediate “pre-calculus” layer vanishes. Logarithms, exponentials, trigonometry, and infinite series are far easier to understand with far less clutter if one learns calculus first. Exponentials are functions that grow at constant relative rates and can be expressed as an infinite series of polynomials. Logarithms are inverse to exponentials and amount to areas under c/x curves. Exponentials of complex numbers move in circles, have trigonometric components, and can easily generate a host of trigonometric identities. For elaboration, see my short book Calculus for the Curious.

The rest of the ordering is similar to the status quo. I just streamline it to focus on one number type at a time. The less jumbled the presentation, the shorter the mental lines between related dots and the fewer the trip-ups in thinking.

The main aim is to introduce more advanced materials sooner. Why? To reflect the permeation of higher math into every major sector of the economy and to make graduates better able to contribute to it. How? Set higher-level goals. Simplify lower-level instruction. Tap new technology to make learning faster and more enjoyable. Reduce attention to skills made obsolete by computers, like long arithmetic calculations, multiplication and division using logarithms, and expertise in trigonometry.

Before moving on, let me acknowledge three features of standard math curricula that mine completely leaves out. The first is recommended ages for teaching the various Levels. I drop that because what gets learned matters far more than when. The less numerate or academically supportive the parents, the longer children will generally take to gain traction at lower Levels. I will say that Level 4 Algebra completion by eighth grade (ages 13-14) seems a reasonable aim even if that occasionally slips by a year or more. A 2021 California proposal to officially defer Algebra 1 to ninth grade was idiotic; kudos to San Francisco voters for urging its offering in eighth grade—the ballot measure passed 82% to 18%.

The second standard feature I drop is the detailed elaboration of what each of the 49 topics should entail. Weaker teachers at weaker schools will likely “teach to the test” for whatever tests are required, while better teachers at better schools will go well beyond. What teachers can best add is sparkle, which comes from teaching math abstractions in an engaging way, and few things smother that faster than detailed recipes mandated from up high. Personally, I prefer at least three curricular approaches—British, Singaporean and Russian—to American norms and wish our educators would study them more. However, given the diversity of American culture and broad resistance to marching in step, acceptance will come easier if we allow “different strokes for different folks” and learn pragmatically what works best.

The third feature I drop is any attention to alleged racial, gender, or socioeconomic characteristics of math. Anyone who thinks there are any shouldn’t be teaching math. Math isn’t even particularly human apart from humans being able to grasp it. Math is universal, and better appreciation of that ought to inspire awe and wonder. For devastating critiques of “woke math” and its consequences, see two articles by Sergiu Klainerman here and here.

Vital Aids

While more advanced and streamlined, the 7-by-7 curriculum won’t do much by itself. Here are four aids I consider vital: integration with coding, certification of competency, grouping by ability, and more parental choice.

Integration with coding means that each of the 49 topics requires students to teach it to a computer. For example, students of the multiplication topic in Level 1 might have a computer build a multiplication table using addition and then check the results using subtraction. ScratchJr is a brilliant, visually engaging, free platform that kindergarteners can easily learn to use. It segues smoothly for older kids into Scratch, more sophisticated and still free. These are wholly adequate for any tasks in Levels 1 through 3. For Levels 4 through 7, I recommend switching to Python, where a dozen free online platforms are available. Between course-provided prompts and AI assistance, writing workable code isn’t the problem. The challenge is to issue appropriate instructions in an appropriate order. To guard against over-reliance on AI, teachers can ask students to explain how and why their submissions work or have them examine faulty instructions and explain what’s wrong.

Integration with coding intends to accomplish three things. First, trying to teach someone else is one of the best ways to learn. Second, it illuminates how electronic brains think, which improves communication with AI. Third, it is potentially fun, a word rarely associated with math homework. Work always goes better when it feels like play.

Competency will be certified at each Level through a standardized test. National standards will be set by a blue-ribbon commission of esteemed professors: half from mathematics proper and half from natural sciences, engineering, medicine and business. Independent companies like the College Board will compete to design appropriate tests, administer them fairly (which includes varying the questions enough to deter use of past tests as answer sheets), and score them. Students can retake tests without penalty but not with the same questions.

Each state will decide for itself which tests to approve and what threshold scores are required to pass them. Between fears of the new regime and political pressures from teachers and advocacy groups, the initial thresholds will likely be low. If graded solely pass/fail, I expect most low thresholds to rise over time once experience attests to feasibility and states compete to lure employers. More likely, better scores will be tagged as honors or high honors and these will become the new standards for admission to STEM-oriented college degrees.

Personally, I see no disgrace in repeated failures at higher Levels. Those students should be offered opportunities to train for skilled blue-collar jobs and encouraged to take them. Ideally every student finds some place they stand tall, at an altitude that depends on both aptitude and attitude.

No restriction on age, grade, or school enrollment will be imposed on test-takers, while passing these seven competency tests will be deemed to fully satisfy the math requirements for high school graduation. The combination will allow highly motivated or talented students to finish more quickly, will free up teacher resources to work with slower students, and will also open a wedge for intra-state competition. Competition will help expose unqualified teachers and prod their retraining or replacement. Competition will also encourage innovation: more engagement, more acceleration overall, and more tailoring of instruction to individual needs.

Certification of competency will facilitate grouping by past achievement and favored learning pace rather than age. That is all I mean by the loaded word “ability”; in particular, I don’t rule out currently slower learners surpassing others later. Kids who have passed Level 3 should proceed to Level 4; why punish them by making them repeat it until slower cohorts catch up? In practice, “No Child Left Behind” means “No Child Run Ahead”, makes everyone slow down, and tends to reward misbehavior. Furthermore, grouping by ability taps the mix of collaboration and competition that is a proven human forte. On the one hand, students of similar ability help each other more because they understand each other better and worry less about free riding. On the other hand, their similarities encourage them to compete even harder to outshine. Like any healthy contest, the point is not to pummel losers but to stretch everyone to their own maximum potential.

Giving parents more choice will enhance competitive feedback. Richer parents already exercise this by moving to better school districts or enrolling their children in private schools. Poorer parents should gain more choice too. At first few will exercise it; the majority will feel too poorly informed to warrant changing or won’t care. Those who do change are in effect experimenting on behalf of all their neighbors. Positive results will encourage emulation.

Obstacles to Revamp

Revamping math instruction isn’t that hard once people realize we need to. Yes, there are bound to be some stumbles along the way, but it won’t take much to improve on the status quo and neither does technology pose significant obstacles. The biggest obstacle is us: our squeamishness about math, our schools’ bureaucratic inertia, and our misplaced sense of social justice. Of course, the “our” doesn’t refer to everyone, and hopefully to none of you readers; I am just acknowledging the prevailing cultural norms.

Every culture tends to ring-fence some areas of life to provide a haven from pressures outside. For example, Germany is very orderly in most respects, even its language is orderly with subordinate verbs stacked at the end, but it keeps its autobahns free of speed limits. America tends to ring-fence its children from hard academic work. While basic arithmetic and algebra skills are deemed necessary, anything higher in math is feared to permanently blight joy. Even in higher socioeconomic circles with parents devoted to their children’s advancement, I rarely detect any enthusiasm for math beyond burnishing a resume for college applications. The main exceptions involve immigrant families from Asia or eastern Europe.

In parents’ defense, many seem amenable to new approaches if schools offer them. Over a decade ago I saw potential for introducing calculus just after algebra, as mentioned above and discussed it in more detail here. To this end I have appealed to a host of high schools and colleges, public and private, privileged and poor, in various parts of the country along with various publicly or privately funded agencies dedicated to raising math skills. All I requested were monitored experiments, for which I would provide written and online materials pro bono and any assistance instructors requested. My years of painstaking efforts were nearly unblemished by success, from which I draw two conclusions. First, my sales skills round to zero. Second, no profession is more averse to learning new things than schoolteachers, save perhaps school administrators.

Why the resistance? It seems that schoolteachers feel stuck in a rut. They were trained in that rut, they’re told to keep teaching in that rut, and the rut is what students expect. Anyone who ventures out of the rut risks blame for any lapses with scant reward for achievements. One of the rare exceptions, depicted with some exaggerations in the 1988 movie Stand and Deliver, involved Jaime Escalante, who shepherded over 100 Mexican-American students from the East Los Angeles barrio to success on Calculus AP exams. However, jealousy of colleagues and administrators’ discomfort with his methods prompted his resignation; math quality at the school rapidly declined thereafter and Escalante never found similar traction elsewhere. Indeed, his later campaign against bilingual education “because I have seen that the language in which the student was going to be successful is English” made many enemies in the teaching association.

Another reason for teachers’ resistance is that they themselves tend to be squeamish about teaching higher math. The great majority either never studied it or forgot what they learned. However, I don’t consider that a major obstacle. There are plenty of good online resources that interested teachers can learn from, including a host of mathematical toys crafted by the global GeoGebra community and easily played with in web browsers. What’s missing are good incentives to learn.

The dearth of incentives partly reflects a misplaced view of social justice. Few Americans think twice about carving out different sports teams for varsity, junior varsity, or intramurals, requiring tryouts for travel teams, or (even if they distinguish between sex genes and gender) about separating girls’ sports competitions from boys’. Yet analogous grouping by math ability is widely decried as apartheid-like tracking. The denunciations do induce more homogeneity within schools, partly by disincentivizing better students and partly by encouraging their parents to move away. The greater the geographic distance, the less it looks like tracking, even though it is often more severe. In 2016, 40% of Black students attended schools that were 90%+ non-white, as did 40% of Hispanic students in 2021. In these schools, which typically have very low standards in math, opposition to tracking penalizes talented Black and Hispanic students. Despite egalitarian intentions, this widens racial disparities in advanced math nationwide.

Black and Hispanic underperformance in math cannot reasonably be blamed on white supremacy, since Asian students in the US tend to significantly outperform whites. Rather, it suggests cultural and class influences that act like genetic factors even if they are wholly environmental. The best antidote would try to offset this through special effort to raise Black and Hispanic math standards, including earlier exposure to higher math and extra acclaim for high performers. Conversely, any lowering of Black and Hispanic math standards seems bound to aggravate racial/ethnic divides, unless coupled with more tracking toward skilled blue-collar jobs.

Jim Crow-like practices of banning darker-skinned students or stripping them of public funding are thankfully long past. The greatest danger now is that standards for Blacks and Hispanic students have been lowered so far that they graduate without developing socially productive skills. That is a huge disservice to them and toxic for society as a whole. It intensifies the correlation between skin color and productive skills that has long plagued American society and exacerbates Bayesian biases, where poorly informed observers impute statistically average characteristics to a whole group.

Ironically, these dangers are currently greater in some historically progressive urban centers than in the old plantation belt. Let’s compare public schools in Chicago and Mississippi. Both are minority white, with Black/Hispanic shares of 35%/47% in Chicago and 48%/4% in Mississippi. Chicago spends 40% more per student than Mississippi does and pays its teachers 60% more (data from ChatGPT and Grok). Yet according to the 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), the shares of Black fourth graders proficient in math was 38% in Mississippi versus 11% in Chicago.

It is not hard to guess why. Chicago public schools have reduced penalties for absenteeism, failures to submit homework, and late submissions of homework. Proposed accountability metrics for schools downgrade test scores in favor of vaguer, subjective measures: “This new system […] shifts focus away from punitive measurements of school quality to a holistic understanding of student learning and wellbeing”. Mississippi in contrast raised academic standards, tested for competency, invested more in teacher training and required more accountability for results.

Still, we need to recognize that even Mississippi's recent advances fall far short of what the US needs. There isn’t that much more economic demand for high-school graduates with good middle-school math schools than there is for the barely numerate. We need to stretch the higher ends too and let their demonstrated know-how inspire more emulation from below. While urban public schools remain far too complacent, I hope that some private schools or suburban public schools will be so eager to outshine that they experiment with some of the proposals I recommend.

Improving instruction one school (your local one) at a time is a great idea.

Early exposure to programming in connection with math ("write a C code for the Euclidean algorithm") is a great idea - too bad these days the task can be outsourced to an AI.

As about the rest, let me sketch an alternative picture.

1. Any revolutionary reform in education ends in a disaster (Examples: "New Math" of the 60-ies, "Fuzzy Math" in the 90-ies). The reason is: education = passing culture from one generation to another, while any reform makes teachers unable to teach and parents unable to help. Only gradual evolution of curriculum can be successful.

2. Totalitarian countries (where individuals exists for the benefits of the society, and not the other way around) have stronger math curricula (the society needs engineers) than democratic ones - where it is easy to make an argument that any particular item should not be taught "because very few people use it in real life". The proposal to replace "pre-calculus" (which is the only common-sense math in the US curriculum) with something "more useful" (such as probability and linear algebra) is, I am afraid, of this nature.

3. Those who think that math of early grades is "easy" and there is not much to learn there are gravely mistaken - read the book "Arithmetic for Parents" by Ron Aharoni of Technion.

4. Problem in the US math education begin in elementary school (by grade 2 former English majors successfully pass their hatred for the subject to their students). Even the excellent (grade 1-6) math curriculum from Singapore turns in the US soil in the absurd of solving 2-step arithmetic problems by labeling "bar diagrams" following an 8-step plan devised by devilish US educators (if you don't believe this, check "Signapore math" in youtube).

5. The mere discussion of how much should be memorized in math indicates the problem: in Russia, kids who prefer math to history say that they like math because "if you understand it, you don't need to memorize anything". And they are right!

6. "Calculus" = "Mathematical Analysis without proofs". It better not be taught at all. Especially in high school, because many will have to spend even more time with it when they retake it in college.

7. The main grade-school level math subject which, if taught properly, teaches theoretical understanding and creative thinking is geometry. As examples for the readers of this post, enjoy the following three math challenges: Using straightedge and compass, construct a triangle given (a) its three medians, (b) its three altitudes, (c) its altitude, median, and the angle bisector drawn from the same vertex.

8. If any curriculum change can be beneficial in the US landscape, it should be replacing the current "consecutive" curriculum structure (algebra-1 - geometry - trigonometry - algebra-2 - precalculus - calculus) with a "concurrent" one, where geometry is taught in parallel with everything else in a span of several years.

Finally, let me comment on math per se: the Pythagorean Theorem. Its proof illustrated in this post (apparently due to Martin Gardner) is indeed the most popular one, but just as most of the other 300+ proofs it is misleading about the nature of the theorem. It is presented as a clever way of cutting-and-tiling geometric shapes, while the theorem is actually about similarity. In the book 5 of his "Elements", Euclid revisits the Pythagorean Theorem (first proved in book 1) and generalizes it this way:

Suppose three figures of the same but arbitrary shape (not necessarily squares) are bult on the sides of a right triangle. Then the areas of the two figures built on the legs add up to the area of the figure built on the hypothenuse.

Since the shapes are arbitrary, no cut-and-tile argument would help. On the other hand, this statement for any one shape (e.g. squares) will imply it for any other shape - for proportionality reasons.

So, why take squares? The altitude dropped from the vertex of the right triangle to its hypotenuse DIVIDES the triangle into two, of the same shape as (i.e. similar to) the whole triangle and built on its legs (as their hypothenuses). That's it: the area of the whole triangle is the sum of the areas of these two parts.

If this exposition sounds too terse, check my article https://sumizdat.com/homepage/papers/eu.pdf - it also contains a Kindergarten-level proof of the standard Pythagorean Theorem which turns out to be about the three similar houses built by the Three Little Pigs.

“Rather, it suggests cultural and class influences that act like genetic factors even if they are wholly environmental.”

At some point America will need to stop studiously ignoring the possibility of genetic factors themselves.