There is considerable anxiety—even panic—among academics regarding the recent White House actions on science policy and funding. The cutting of overhead rates on federal grants, the massive layoffs in funding agencies, the suspension of operations at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the freezing/auditing of some programs have created financial uncertainty and disruption for many researchers. Doomsday forecasts for the future of American science abound and crowds are taking to the streets to “march for science.” So is American science dying at the hands of DOGE? The disruption and uncertainty created by the recent measures are undeniable and cause for concern. Yet, I also see an opportunity to address a deeper systemic problem plaguing science: American science is dying from bureaucracy—and if the DOGE crew can channel their energy into yanking science from the grip of this malady, we will all end up in a better place. What follows is a report from the trenches—what it is like to carry out research at an American university. I focus on various aspects of securing funding (using the National Science Foundation (NSF) as an example) and carrying out routine tasks of research administration.

I submitted my first NSF grant in 1999. Back then, the submission process was simple and straightforward. The PI had to produce the actual proposal (a 15-page narrative plus references), an itemized budget, a short budget justification, a two-page biographical sketch (listing degrees, professional appointments, and no more than 10 publications), a list of current and pending funding, and a brief description of facilities and equipment available to the PI. The proposal was uploaded to an online system (called “Fastlane”), which was easy to use—the PI had to upload pdf files to the portal and fill in a couple of pages of simple forms. The institutional (university) approval process entailed checking the budget—to make sure that budget categories, salaries, fringe benefits, and overhead were correct.

Post-award administrative duties were also quite light. The PI would tell an administrative assistant which students or postdocs to put on the grant, approve (verbally or by email) routine expenses (travel reimbursements, lab supply purchases, etc.), and pay invoices for equipment purchases. Reporting on the grants entailed submitting a half-page free-form narrative plus a list of publications acknowledging the grant.

The light PI duties meant that the administrative support provided by the university could also be light—the PI needed the help of just one admin to set up salaries, order equipment, and manage travel reimbursements.

Fast forward to 2025—things are very different! The bureaucracy around funded research has reached insane levels. The burden on the PI is crushing. Management of the grant submission process, reporting, and administration of the research now involves massive internal bureaucracy comprising multiple online platforms (each with their own maddening idiosyncrasies) and multiple levels of admins—a few that help PIs deal with administrative and clerical tasks, and many, many more to check boxes, count beans, and oversee the execution of various compliance tasks. Not only does this bureaucracy consume valuable time—its costs contribute to the institutional overhead of the sponsored research.

Below I highlight the inane bureaucratic aspects of doing research at an American university. Some come from funding agencies (I use the NSF as an example, but other agencies have their own unique requirements), and some are internal university procedures. I am not 100% sure which elements are internal university dysfunction and over-compliance and which are mandated by the government. Every time I ask why I should do this or that, the answer is always “to satisfy federal mandates.”

I recently finished submitting a single-PI NSF proposal. I spent days dealing with various bureaucratic steps, troubleshooting glitches on several online platforms, and navigating the byzantine procedures of grant submission. Completing the task required the help of three trained admins.

The proposal now includes numerous non-scientific documents—the entire package was 64 pages long, of which only 15 were scientific narrative (which included a mandatory Broader Impacts section) and 10 were references. In addition, the proposal must now include:

A mentoring plan (an enumeration of banalities, such as statements of commitment to advise postdocs on which conferences to attend and how to approach the next steps of their career);

A list of the PI’s synergistic activities (describing service to the profession—such as editorial work or conference organizing, which we used to include as a short section in the biographical sketch);

A data management plan (again, a meaningless enumeration of trivialities and platitudes—such as a statement that the researchers will back up their data and share their research results as appropriate);

A conflict-of-interest spreadsheet listing collaborators and former associates in a specific format (mine has close to 200 entries).

The best collective description of these supplements I can think of is this: “We don’t trust scientists to do their job properly—it is the role of the NSF to nanny and micromanage every aspect of their day-to-day work.”

Larger collaborative proposals include even more supplements—such as a DEI plan, a management plan, a statement of intent to carry out the proposed research from each PI (as if someone would spend weeks writing a proposal without the intent of actually doing the research if it is funded), and a statement of work for each PI (generally repeating what is already described in the proposal). Some programs even require the PIs to include a Code of Conduct, plans for ensuring “Safe and Inclusive Working Environments for Off-Campus or Off-Site Research,” and/or a “Safe and Inclusive Fieldwork Plan.”

The process of grant submission

The grant is submitted via the research.gov portal, which—unlike Fastlane—is very cumbersome and therefore requires a specially trained admin to deal with (despite my having 25 years of research experience under my belt, I am incapable of handling it on my own). Since last year, the portal uses dual authentication. This means that the PI cannot just give her credentials to admins so that they can work with the system and input the data. Instead, there is a complicated process the PI and admins must go through in order to grant the admins access. Setting this up took three days working with at least three USC admins and communicating with the research.gov support team.

The requirements for documents have also become insanely specific—I would even say petty. For example, the biographical sketch now needs to be prepared using yet another web portal (SciENcv) in which the required data must be entered in little boxes. The PI needs to create an account for herself, and then, in order to delegate the task of data entry to an admin, must go through another involved process of adding the admin to the system. Once the data are entered, the PI must login again and “certify” it before the generated biographical sketch can be uploaded to research.gov. The upshot of all this is that something that formerly required minimal effort of the PI—10 minutes tops—has now become a significant task requiring hours of combined effort of the PI and several admins (compare my most recent biographical sketch prepared through this procedure with my biographical sketch from 2012 and see if you can find any justification for the more complicated procedures and the accompanying cost of implementation).

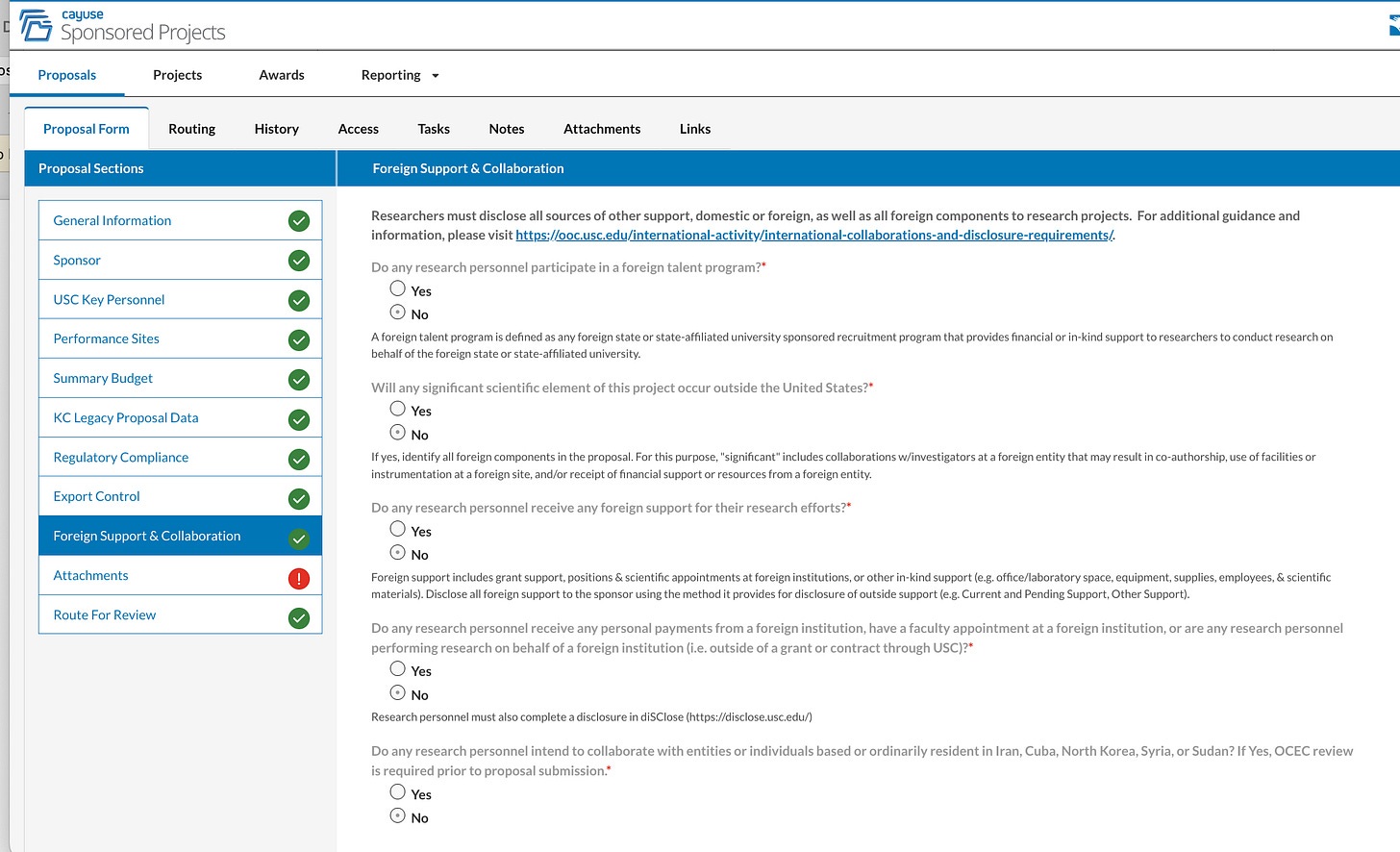

The institutional approval process now involves an internal web portal where the PI and her admins need to answer pages of compliance questions—such as disclosing international collaborations, intentions to travel internationally, etc. Even with the help of a dedicated and skilled admin, the process of internal approval requires multiple logins (each one using dual authentication) to click a multitude of “approve” buttons. Although each of these mindless steps is small, together they add up to a considerable drain of time.

In addition, the PI must be current with internal requirements for reporting real and imaginary conflicts of interests (as a USC lawyer put it at a faculty meeting, “There is never such thing as too little to disclose.”) The disclosures involve yet another internal online portal with many little windows to enter answers to inane questions, and another cluster of admins to review and pass judgement on the answers. Sometimes there are mandatory trainings to take.

Research administration and post-award activities

This is really when the PI gets seriously punished for doing her science!

Internal hurdles

Every semester the PI and her students and postdocs must certify their efforts—that is, confirm that they actually did work on the research supported by the grant. This requires a dedicated admin to prepare certification documents for each student and postdoc, and then the PI and postdocs logging into another platform and clicking through several incomprehensible screens.

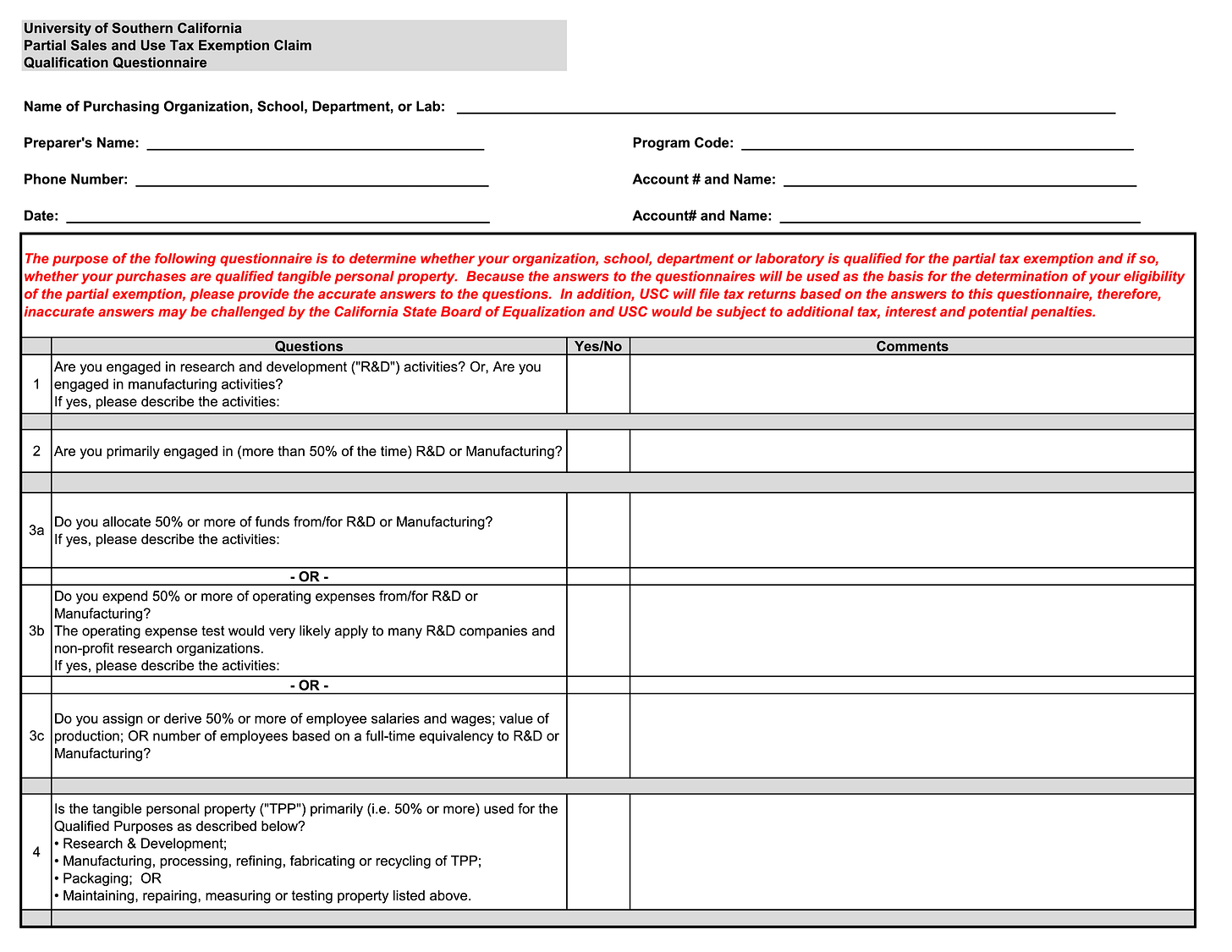

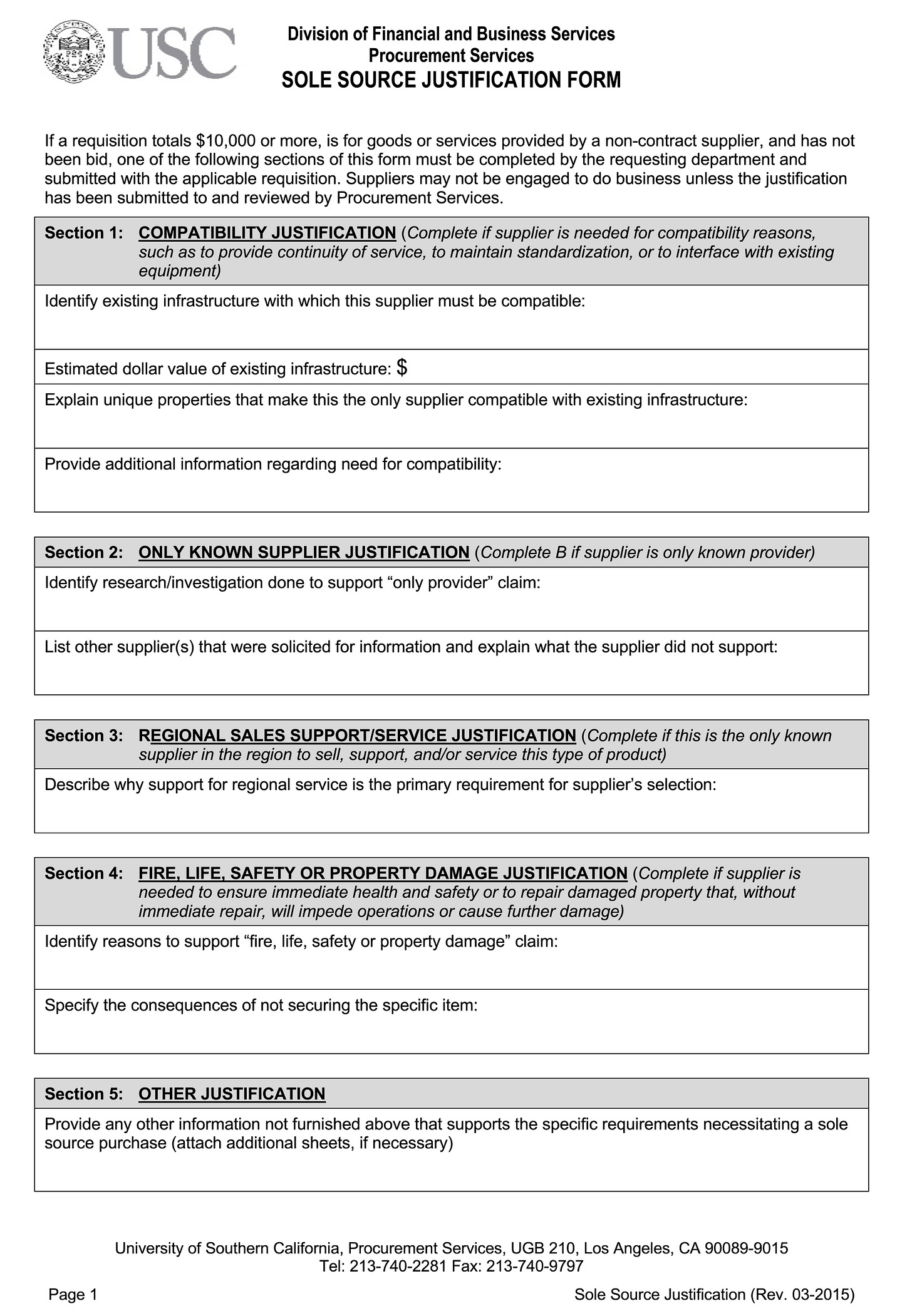

Ordering equipment requires multiple steps such as filling out inane forms explaining why you need the equipment, justification of the choice of vendor, whether the equipment complies with a litany of internal policies (such as these ITS policies), and so on. Two such forms are shown below.

Some equipment—such as laptops and other electronics—is subject to scrutiny by the bloated ITS bureaucracy, which is empowered to make decisions for the researchers despite having zero competence in the subject matter of PI’s work. Purchasing USB flash drives for undergraduate chemistry labs can turn into a protracted power struggle involving meetings with the ITS and risk management departments, forms, requests, and appeals to the highest-levels of the administration—and the outcome of all that is uncertain (our department lost such a fight and was not allowed to procure the most-economical and most-suitable equipment). Purchasing laptops using research funds is now impossible and I and my students and postdocs use personal funds for these essential tools for our work. The current policy at our university is that all laptops purchased using grant money must be under complete control of ITS—they control laptops remotely; limit what software you can install; have access to all your data; can update, reboot, or wipe out your device as they please; and can lock you out of your own computer by disabling your login credentials. The latter scenario is not hypothetical—if the device is non-compliant with USC’s policy standards and the user is non-compliant in remediation, ITS will lock the device.

Travel reimbursements involve entering fine-grained data (e.g., hotel expenses need to be entered day by day, with room charges and taxes entered separately) in another web system, providing multiple proofs for each expense (the paid bills or conference registration invoice are not sufficient). Each reimbursement is subjected to multiple levels of scrutiny—and the bean counters always find a way to send it back to the PI with ever more aggressive demands.

Since my research in theoretical chemistry does not involve people, animals, or field work, I do not have to deal with IRBs—the stifling role these bureaucracies play is a whole separate topic (see, for example, here, here, and here).

Hiring postdocs

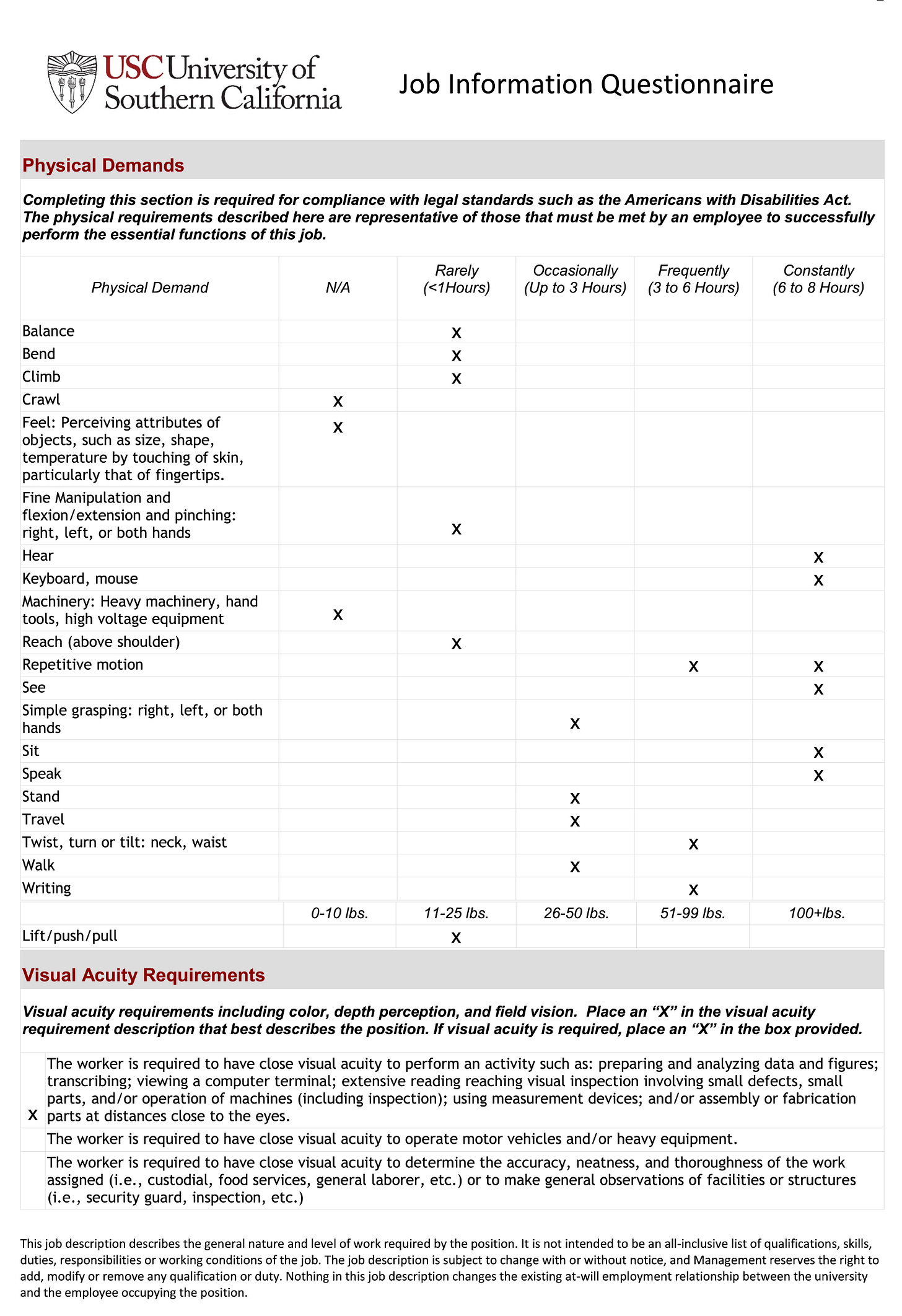

The process is very involved and requires interactions with a bloated HR department, which makes hiring difficult and firing impossible. The process requires the help of several departmental admins—and I do not even know how many bureaucrats are administering it from the HR side. The job advertisement needs to follow a specific template and be posted on a special portal. The PI needs to explain why she did not interview every applicant who claimed to have appropriate expertise. In addition, there are more forms to fill out—including, for example, checking boxes specifying whether, and how often, the prospective theoretical chemistry hire will need to run, crawl, reach above their shoulders, and so on (exhibit below and here). For international hires, there is another layer of visa-related paperwork.

Managing postdocs

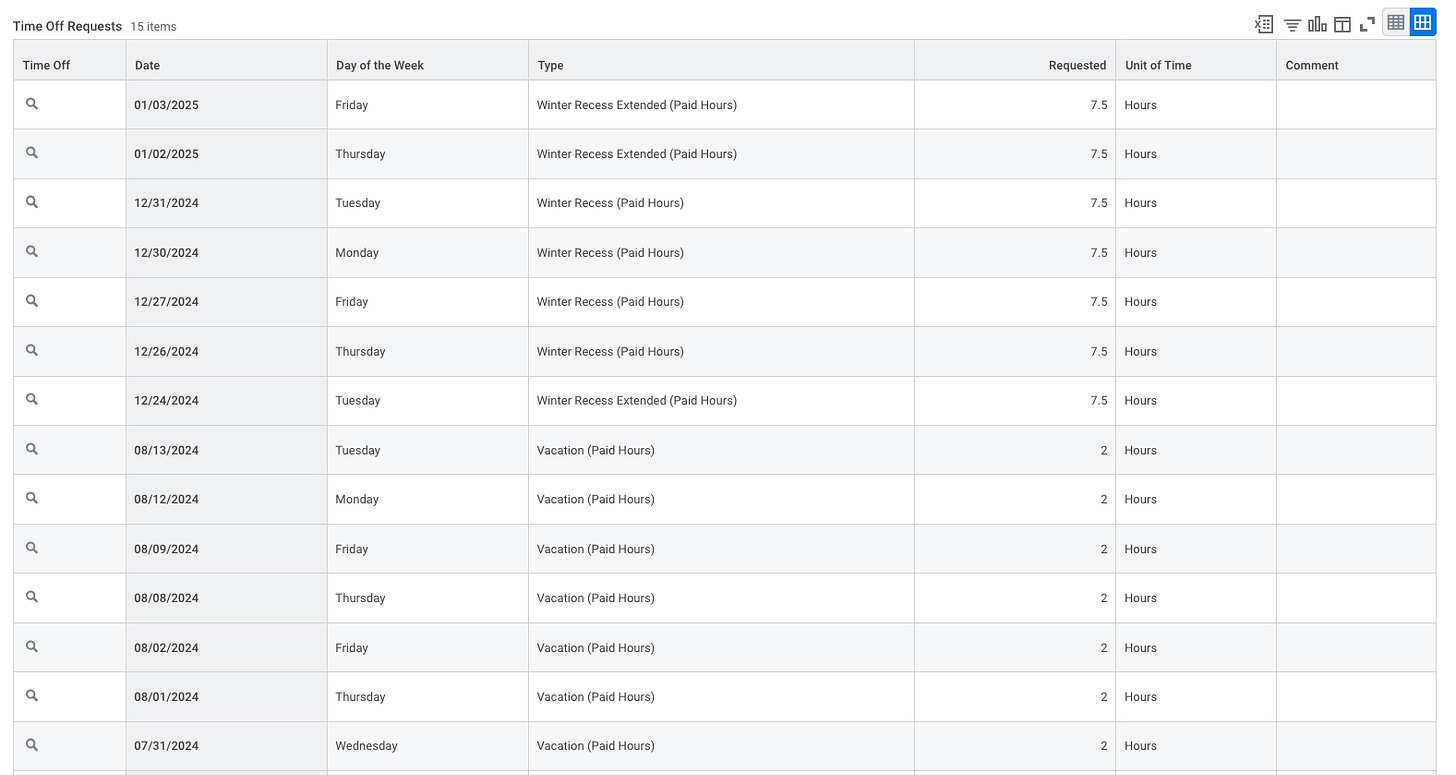

Postdocs are entitled to vacation time. This is managed through the internal HR portal (“Workday”), where postdocs must input their request for time off (in parcels of 7.5 hours or less—see the screenshot below), and the PI must log in and approve the requests. Christmas break time needs to be explicitly entered and approved. If this is not done through the system, the PI is obligated to pay for the “unused vacation time” when the postdoc leaves employment regardless of whether the postdoc used (or even exceeded) their allowed time off. For international postdocs who have OPT (Optional Practical Training) status, the PI is required to file additional paperwork not only when the postdoc is hired but also when their contract is renewed.

Reporting

This is a big item on the PI torture rack—and it requires the help of several skilled admins, in addition to the PI’s effort.

Reports are managed by grants.gov. The PI must submit annual reports and a final report (that means four reports for a three year grant). Each report entails entering bits and pieces of narratives into multiple windows—about two dozen of them. Each window has a prompt—often inane. For example, there are separate boxes for “Significant Results” and for “Key Outcomes or Other Achievements”—what the difference is between the two still baffles me.

Each report requires listing all paid personnel by name, specifying their time dedicated to the project, and their specific role. The preparation of this requires the effort of a dedicated admin who needs to go and pull out the payroll data. After the report is submitted, the system sends emails to the personnel asking them to supply demographic information.

Reporting products of the research—such as publications—is another trial. The PI cannot simply submit a list of publications acknowledging the grant. Rather, each paper needs to be uploaded to a special government database (the NSF Public Access Repository for NSF-supported research). For that, a file of “just accepted” (but not finally published) manuscript needs to be prepared and converted to ADA-compliant format by means of a multistep process requiring a trained admin. In addition, details of each publication need to be entered into boxes. The more papers you publish, the more you suffer.

You can find an example of an annual report from my grant here.

In summary

The bloat of bureaucratic procedures around funded research is costly in time, effort, and frustration. The procedures are ineffective and pointless. These requirements do not lead to better science—they suck energy and money. We need to treat PIs as competent and responsible adults and stop wasting resources on micromanaging and bean-counting. Specifically, I propose the following.

Funding agencies:

Return to a bare minimum proposal package (circa 1999) and eliminate all these b*s* supplements.

Abolish SciENcv and allow PIs to provide data in free format—the simple 2-page biographical sketch served us well. (A glimmer of hope: the morning after Jay Bhattacharya’s successful confirmation, NIH issued a notice postponing the transition to “Common Forms for Biographical Sketch and Current and Pending (Other) Support”—the wretched online system I had to use to prepare my biographical sketch for my NSF proposal. The PIs are still required to use templates though).

Limit annual reporting to a list of publications with DOIs and an optional half-page narrative.

Cease collecting demographic information.

Abandon federal databases, such as the NSF Public Access Repository with ADA-compliant pdfs of just-accepted papers.

Cease invasive micromanaging research operation and scientific activities—no more codes of conduct or plans for inclusive work environment.

Eliminate federal requirements for mandatory trainings, certifications, disclosures, hiring procedures, and other forms of red tape and bean-counting.

Simplify the research.gov portal (remove dual authentication, etc.).

Universities:

Cut out costly internal bureaucracies and treat faculty as adults. Don’t nanny them—let them manage their research labs in the way they find optimal.

Cut out over-compliance—follow common sense procedures.

Restore ITS to what it used to be—a provider of IT services. They have no business controlling equipment and operation of research and teaching labs.

Make reimbursements simple again! The documentation required by universities for routine travel expenses should not be more extensive than the documentation required by the IRS for tax-deductible expenses.

Accept reasonable operational risks—bulletproof (over)-compliance is not the answer. Nannying faculty is not the answer. Policing software installation on our laptops is not the answer. If an individual faculty member violates federal regulations or engages in ethical misconduct—hold them accountable and leave the rest of us alone. If a researcher makes a mistake in managing her equipment—she can bear the consequences.

By taking these steps, we can begin to reform our institutions and restore the environment of free inquiry, intellectual courage, creativity, and innovation that propelled American science to its historical successes.

I recently applied for a grant for which my collaborators and I had to detail our plan for broadening participation in computing. We had to pledge to be involved in “high school math contests for women and gender minorities,” gathered data on demographics of students served by these, participate in summer research programs for undergraduates from under-represented groups, again collecting demographics and running our own little sociological analyses, and pledge to go to extreme efforts to recruit women grad students. Three pages of this stuff! I just want to work with my colleagues and do research; I don’t want to have to adhere to someone else’s social justice agenda as part of getting funding for research. (Whether I agree with the agenda or not, I don’t want it tied to funding for scientific endeavors.)

I’m so glad you wrote out all the steps we academics go through to maybe receive federal funding. Folks need to know what these processes are like.

During my fifty years working at a university, the requirements for research became ever more onerous. Working in the social sciences with human subjects, I was, toward the end of that period, subject to "ethics" bureaucrats who would judge applications and give or withhold their permission to submit a grant application or to continue with the research project. Exactly what political criteria were used to decide on a project's merits was not always made clear, but political correctness seemed paramount. But these administrative bureaucrats seemed to savour putting the professors in their (subordinate) place. At the end of my time, each researcher was required to take an on-line ethics course, filled with politically correct and far left "ethics," which, without having passed, you could not receive permission for your project. One of the rules was, you cannot impose any tasks on an unwilling member of your research team or subject group, although that is exactly what the requirement for the ethics test did with the RI.