Extreme emphasis on sexual harassment stifles productive scientific discourse between men and women

by Luana Maroja

In 2019 my professional society (The Society for the Study of Evolution - SSE) hired a consultant to help “prevent sexual harassment at the [annual] conference.” The initiative consisted of training volunteers to be “allies” (they got buttons and walked among us signaling their role as meeting police), projecting messages (powerpoint slides) on the walls of the poster session saying “stop harassment now,” and putting posters in all bathrooms along with anonymous boxes for depositing complaints about harassment. This came at a cost: about $10 dollars increase in registration fees per participant, resulting in tens of thousands in the consultant’s pocket. But aside from cost, are these initiatives a net positive or a net negative for scientific interactions?

I have been attending the SSE meetings since 2003. Compared to conferences in my home country, Brazil, SSE conferences were a paradise – nobody ever grabbed my rear end, said nasty things in my ear or followed me around. Yes, there was the normal degree of flirting, but it was polite, with people backing off when they were rebuffed. Perhaps I have thick skin, but I don’t think anyone would say that serious harassment or sexual violence were commonplace at the American meetings, and there were already procedures in place—involving both the local police and the conference administrators—to deal with serious offences. Many people think it’s a good thing to raise awareness about even minor actions that might be perceived as unwanted attention. But is it?

When I saw what the organizers were doing, I was immediately concerned about the chilling effect it would have on interactions between the sexes. In my life I have benefited from great relationships with my male advisor and other senior male researchers. I would not want men to be afraid of talking, interacting and collaborating with me merely because their actions might be misinterpreted. Wondering if men were actually more cautious about interacting with women and in particular junior women (in general, not only at conferences), I started asking around. As I expected, many men secretly confided to me that yes, they do not volunteer to mentor junior women and are circumspect when talking to junior women PhD students out of fear of misinterpretation. I could swear I even saw people taking a step back as the “police allies” walked past them! However, my sample is not only small, but biased – I could ask only men I already knew well and was friendly with, not a random sample of the research population. But now we have data – the first study looking at the effects of the #MeToo movement on female research collaborations in economics: Gertsberg, Marina, The Unintended Consequences of #MeToo: Evidence from Research Collaborations (May 10, 2022). Available at SRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4105976 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4105976

It comes as no surprise that the #MeToo movement did indeed reduce the number of scientific collaborations between men and women, especially the establishment of new ones. Fig. 2b from the paper (below) shows the changes in number of new male co-authors with junior female authors during the #MeToo movement. The light bars on the left side of the graph show the number of pre- #MeToo new collaborators, while the dark bars show post-#MeToo collaborators. These include new male authors both inside and outside of institutions – the reduction of new male collaborators inside institutions is large and significant. The right panel shows existing collaborations before and after the movement, these do not change as much in the between the pre- and post-#MeToo, although there is a reduction on existing outside collaborations.

The data shows clearly that new collaborations are strongly and significantly reduced inside institutions (where the fear of harassment accusations will be highest). The paper also shows that, where the fear is highest (in institutions where harassment accusations are common and policies are vague), the reduction in collaborations is also higher.

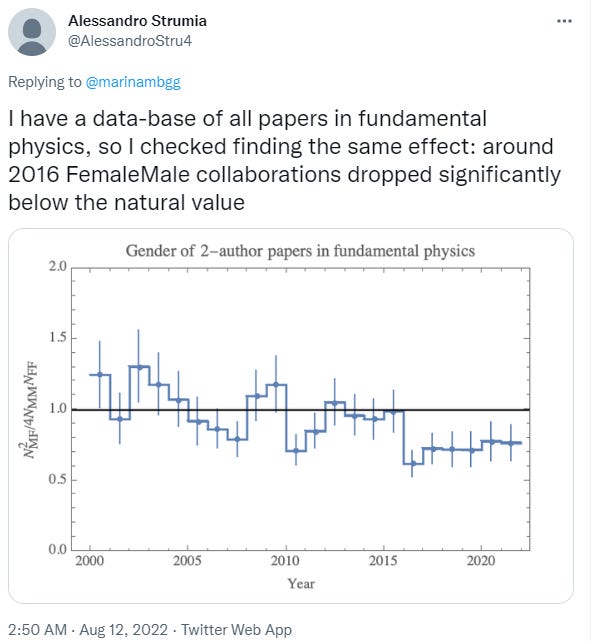

This represents a huge loss to both men and women, but it especially harms women. Indeed, the academic output of females fell significantly after #MeToo (a decrease of between 0.7-1.7 projects per year, with the loss in male collaborators explaining 60% of this decline), while the output of males did not (they were apparently able to find other male collaborators). This decrease in collaboration is apparently also happening in other fields, such as fundamental physics – below is a plot from a tweet showing a significant decrease of female collaborations with males on scientific papers between 2000 and 2020.

It’s clear that well-intentioned actions (protecting women from harassment) can be taken too far. I hope that our scientific professional societies will absorb these data and start taking steps to bring people together rather than separate them. Good starts would be clarifying harassment policies and keeping “harassment consultants”, who profit from promoting the idea that harassment is everywhere, out of conferences. Another important step would be to eliminate anonymous complaints, which set the bar for a complaint too low and can be used for revenge and to bring down competitors and enemies. Both of these effects lead men to worry about what they might be accused of and to thus limit interactions with women. Finally, any sexual harassment judgements should only be made after a pre-defined, fair process where the accused can challenge the accuser– a person should be considered innocent until proven guilty.

Excellent review of an important study! I had such concerns - that this fixation on sexual harassment and #MeToo hysteria will poison the climate and ultimately hurt women professionally. And everyone socially -- by making professional interactions less fun. And here it is -- the data show exactly that. We should fight against this. I complained about ACS flashing opening slides with hoteline numbers for anonymous reporting and statements of zero tolerance to sexual harassment. This time around (Fall ACS meeting) there are no such slides, although there are signs in the halls with things like "see something - say something."

In the following sentence accompanying Fig 2, it appears as through the words "light" and "dark" should be reversed.

"The light bars on the left side of the graph show the number of pre- #MeToo new collaborators, while the dark bars show post-#MeToo collaborators."